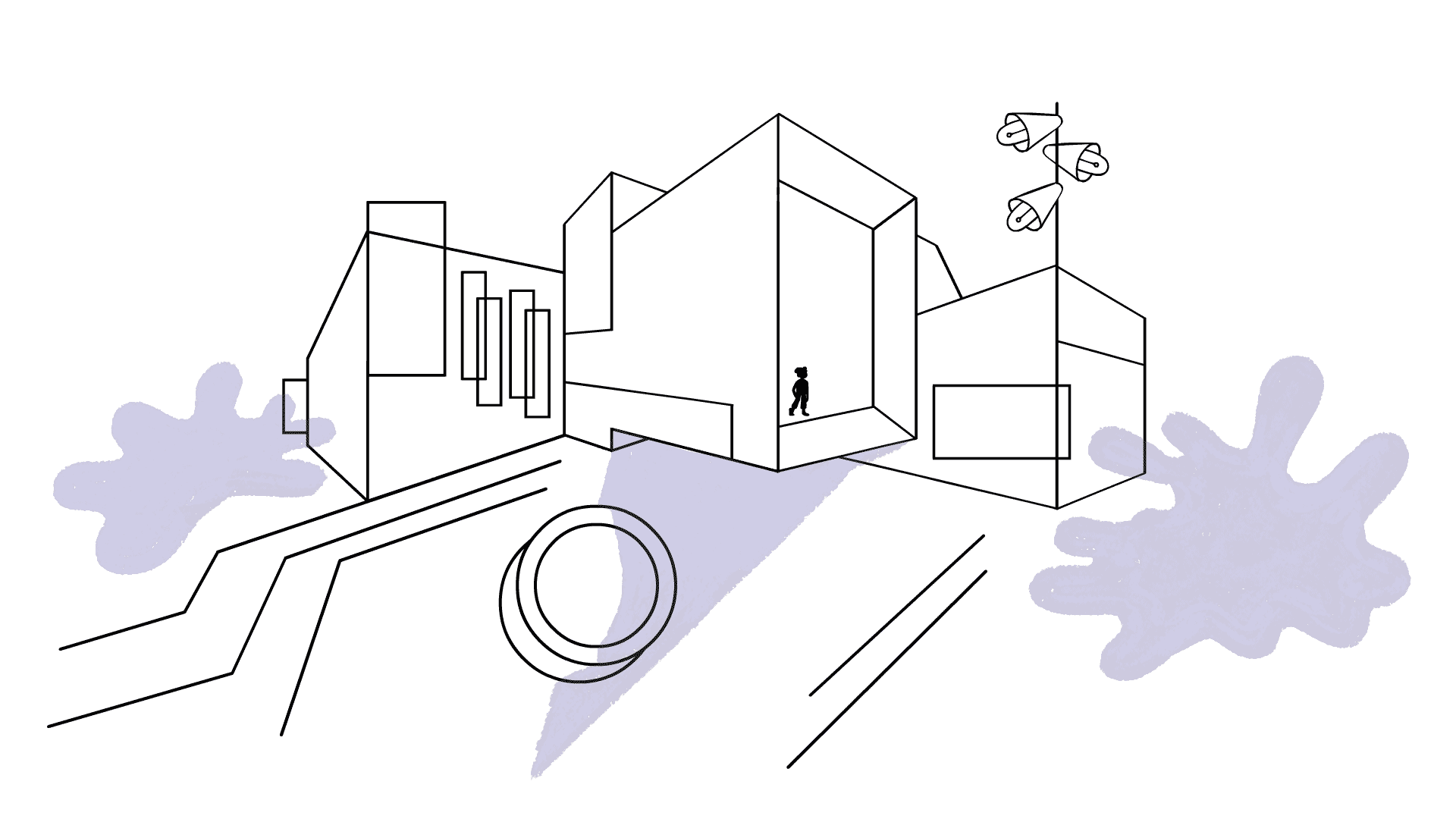

The white, brightly lit monolith of the new Emily Carr University of Art + Design campus rears out of the dim beside Great Northern Way. The south side is separated from the road by a building still encased in scaffolding, a banner hung on the side reveals the building’s branding as a new office space: “South Flatz: A Community that Inspirez.” Tucked behind is one of the entrances to ECUAD itself, but you’ll have to walk through Chip and Shannon Wilson Plaza first –– names you may know because Chip Wilson founded Lululemon and their family real estate company, Low Tide Properties, is a big player in the buying up of property along East Hastings in Strathcona. The campus sits amidst the redeveloped False Creek Flats, once a rail yard and industrial area, now a hotbed of construction for the city’s projected tech hub.

I meet with a group of ECUAD students including Ali Bosley, Theo Terry, Aubin Kwon, Z* and D* who have come together to strategize about voicing student concerns around the new campus. They call themselves the Emily Carr Student Action Group. In November, Terry created a public Facebook event called “Alternative Open House,” which was intended to overlap with the official unveiling of the campus to students, general public, and financial stakeholders. The event was organized to address the unrest that swelled in many returning students when they move into the new space.

“We arrived [at the new campus] and it seemed like a significant change [occurred] in the value of artistic production, and sort of the role of the artists that they are trying to produce here,” says Terry. “It seemed in many ways like the school wasn’t built for students: it kind of feels in some way like it’s a showroom for artistic production.”

Plans for ECUAD to move to a different campus began sixteen years ago, ample time to ensure that planners, architects, and the institution itself were on the same page about what an art school should look like. However, students are still encountering one of the major setbacks of their former Granville Island home: inadequate space to work in.

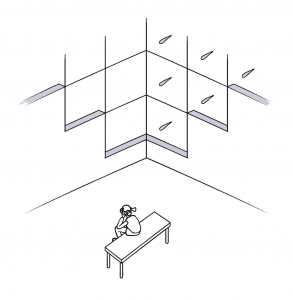

“I think there’s a lack of understanding of what the students need and of what each department needs,” says Bosley. Rather than building studio spaces where students can store their supplies and works in progress, the architectural focus of the school is clearly on wide hallways, massive common areas, and showy lobby spaces. “There are so many spots in this campus that are open spaces,” says D, “I’m thinking: ‘You could have added another floor and added more studio space […] instead of having this giant atrium with a million-dollar view.’”

Students have found themselves delegating space amongst each other. “You cannot imagine the disruption that having to navigate a space causes in someone’s practice,” says Z, who’s found herself painting at home and commuting with wet canvases. D tells me that she has had to invest in an off-site studio space, on top of her tuition. A move to accommodate design and tech-focused art education, “marketable arts” as Z terms it, is a palpable undercurrent in the school’s structure and branding.

Among one of the larger issues hanging over the campus and its students is the heavy involvement of big-name donors from the private sector, many known real estate developers complicit in the gentrification and re-shaping of Vancouver; donors who haven’t been open to discussing the shortfalls of the building they invested in.

Though the student union donated $325,000 towards the construction of the new campus, and contributions to the school have been made by alumni and faculty, the administration’s focus appears to be on venerating their wealthy donors. Hoping to reduce the budget allocated to the arts, the provincial government made the switch to a private public partnership (P3) method of funding infrastructure for the new campus. This means that the school is relying on the “patronage” and economic interest of potentially problematic private donors and investors. Bosley equates the relationship to attempting to speak with an unforgiving landlord: “You’re made to feel ashamed of wanting more space and needing more space,” she says, “[You’re] being asked to adjust your practice or your lifestyle because you should be grateful for being in this space.”

The structural shortcomings of the new campus and the administration’s reluctance to acknowledge it places students in the role of cultural workforce, and demeans the importance of artistic process, growth and education. “What we’re looking for in the longterm is changing this notion that the only value of art is economic value,” Terry says. D agrees, “It’s about voicing concern for the life of art and culture in Vancouver.” This article can only scratch the surface of the complexity of the structures of power in place over ECUAD, and, by extension, the independent arts scene in Vancouver.

With a shortened semester, lack of space, and anxiety surrounding speaking out, it can seem impossible to gather the energy and the resources needed to fight back against the agenda of those who hold the economic power in the city, and influence at the new ECUAD campus. Stakeholders, however, are just that: they took a financial risk, and the measures being taken to congratulate them on that risk encourage the donors to feel that they have made a good investment. “Arts spaces are always used as enrichment for the community,” notes Kwon. “Developers will invest in public art and it becomes the thing that justifies gentrification. [The investors] are very concerned with the image of this being the centre of art creation because that image is a really strong basis for developments and for attracting people to invest in the community.”

The reality of the ECUAD campus is that it is becoming inhospitable for fine arts students, and the only way to preserve the kind of fine arts education that the school has provided for nearly 100 years is to activate the student body, and to take up space in the school and in the community. Vancouver’s artists are already required to fight for their practice, and there is no doubt that the obstacles facing ECUAD students will evoke resilience.

“I want people to know, people who are coming to school here and who are new to Vancouver, that the arts community here is so rich and so tenacious in this city,” says Bosley. “I want them to come out of this experience being okay to say no to things, to be okay to ask for things that they need, and knowing it’s okay to voice their concerns.”

X

*Names have been changed.