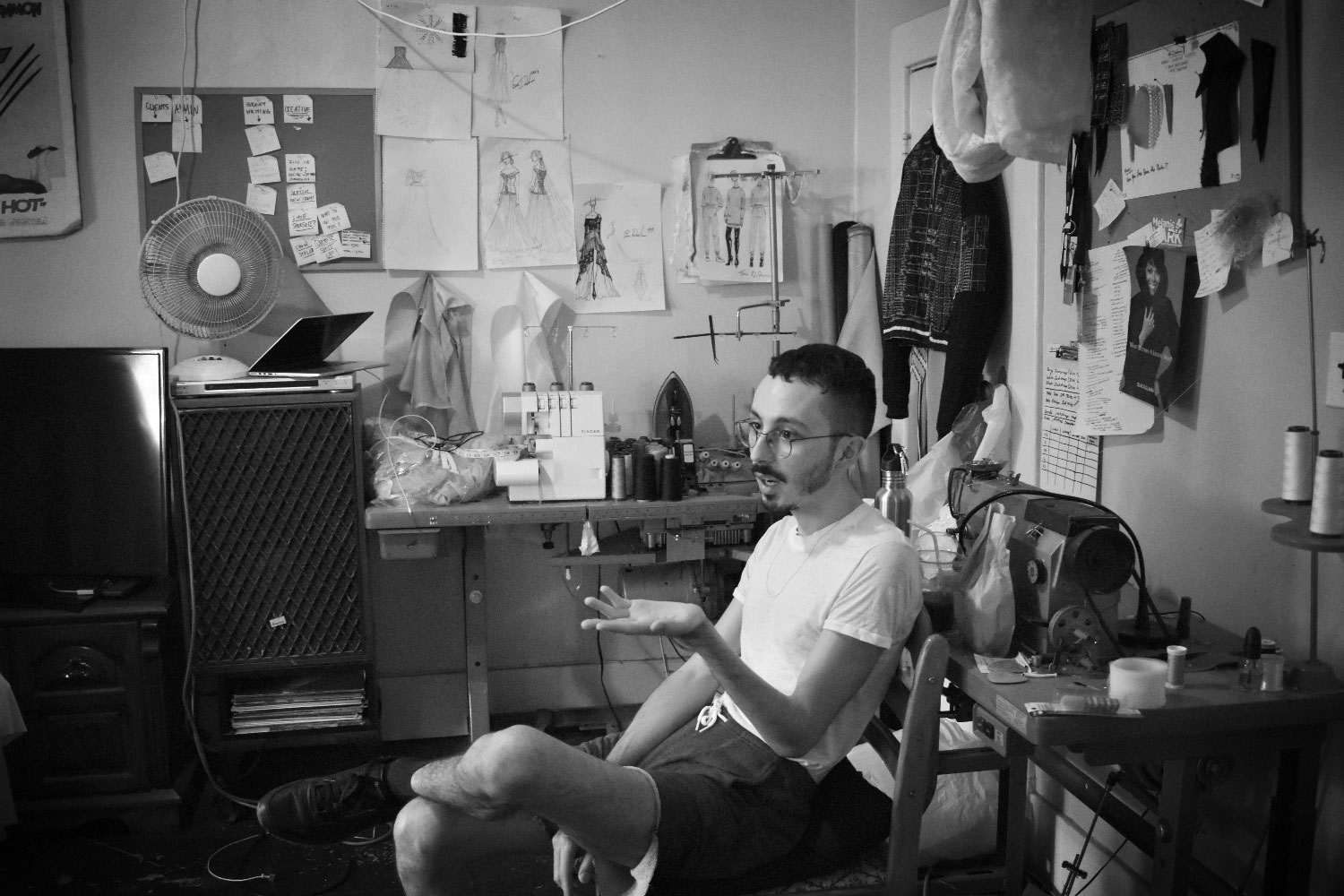

“I’m a relatively white-passing, queer-Métis boy who grew up in the country, entrenched in culture, surrounded by family, feminine strength, masculine strength and just strength in general, and that’s what I talk about in my work,” expresses designer, Evan Ducharme. Mid-day sun streaks into his studio, an artfully infused room in a East Vancouver heritage home. His work is draped all around us; there are sketches on the walls, orders in bags, and a proud mannequin wearing a culturally informed wedding dress that Evan is designing for his cousin.

From Vancouver Indigenous Fashion Week to Indigenous Fashion Week Toronto to a feature in Vogue, Evan’s stunning designs and confronting patterns are forward-thinking and intricately dialogical. Evan may identify as a Vancouver-based queer-Métis fashion designer, but his work is much more complex than any label could imply. We use these descriptors to address people who deviate from the “norm,” but it must be acknowledged that these labels come with colonial connotations. The very ethics of Evan’s brand work to destabilize stereotypes of Indigeneity, sexuality and fashion, which have been defined under colonialism.

Since Evan graduated from design school in 2012, his career has had a constant trajectory. In 2014, Evan gained greater public attention with collections, Halcyon and Iconoclast. In 2015, Saudade challenged Evan to reconsider the perception of sexuality in colonial and ancestral contexts. The following two collections, Origin and Atavism were more politically informed. Evan explains that Origin (2016) “was really about me reclaiming traditionally male roles that I wasn’t a part of as a kid and thinking about the barriers of queer folk in traditional communities.”

Before anything, Evan expresses the importance of honouring his Métis ancestors. “Our relation to our ancestors does not end when that person is no longer in their body. This person still contributes to your life in very meaningful ways, and [you] really have this strong sense of relationality to them, and that’s never not going to be present in my work,” he says. But as Evan explains, this ancestral influence “might not be there in visual ways. They might be more in the research and in the ethical methodologies that I use within my company.” He continues, “There’s always going to be what some would consider a very strict code of ethics for what we do, and how I interpret my own culture for a customer that might not be Indigenous.”

Evan’s most recent collection, Atavism (2017) opened a platform for discussion with the use of a fabric patterned with a census print from 1916. It replicates a document where Evan’s grandfather’s name is listed, followed by his racial identity which was initially classified “French,” but was scratched out and re-labelled “Indian.” Evan says, “This was my first collection where I spoke explicitly about my Métis identity.”

Evan explains that Atavism was “really all about survival and thriving in the midst of hardship.” The term comes from a Western scientific root describing biological traits inherited from ancestors that re-emerge after lying dormant. “My culture has been alive and thriving, multiplying and changing. […] That’s just the nature of Indigenous culture. We were forced to adapt to what was thrown at us,” Evan explains.

With a consciousness of the pervading nature of colonialism, Evan stresses that “decolonization is a process, not a destination.” Being educated within the Western fashion system, he admits that his own training has been infiltrated by colonial impressions, particularly around body image. “I’ve spoken to a lot of people who don’t fit into the visuals that I put out into my company and it’s really been unsettling to me that I’ve been perpetuating this fashion industry standard. […] Those sets of ideas about what is beautiful is something I’m actively working on right now. Within the next season, there will be a lot more visual representation of different bodies,” says Evan.

Evan’s new collection aims to conceptualize the joy of being Métis. “Just lately, I’ve been thinking about this notion that Indigenous artists in general have to lay bare their struggle and their trauma to validate their work,” explains Evan. Although he admits these experiences need to be shared, he believes in holding space for the celebration of diverse First Nations, Métis and Inuit identities.

“I was extremely lucky to grow up where I did. I was very entrenched in my culture, entrenched in that sense in family,” explains Evan. “I don’t think that folks are used to seeing a very confident self-assured Native person. It’s almost [as if they’re] like, ‘You should know your place.’ I know my place. My people suffered immensely for me to be able to stand here confident and speak, for them to speak through me.”

It’s clear that Evan’s experience is not independent of his ancestors, but that their presence in his life is not only inherent but vital: “I always think back to this Maya Angelou poem where she says: ‘I enter as one, but I stand as 10,000.’” Enlightened by his ancestors, Evan redesigns what it means to be queer and Métis in the contemporary world.

x

Evan will be a guest speaker at Ancestral Inheritance, an event taking place on August 12 as part of the Vancouver Queer Film Festival. To see his designs, visit evanducharme.com and follow him on Instagram @evanducharmestudio.