I was a cute kid. I had these big chubby cheeks that squished my eyes into two upside crescent moons when I laughed. I had a belly and rolls on my thighs and arms. Basically, I was a little halfbreed bonhomme, and I was adorable. Unfortunately, baby fat does not translate well into adolescence and I remember the first time I was made aware that I had a body. I mean, I always knew I had a body, it was the vessel that let me shove dino shaped chicken nuggets into it and transported me around the playground. But, my body was never something that I was aware of, let alone, something that others were aware of.

So, picture this, I’m in grade three, and we are playing dodgeball. The most coveted game of gym class. Grade three was probably the last time I felt tall. I towered over the boys in my class, and because I was a chubby kid, I also outsized them. We are playing dodgeball, it was heated, red foam balls are flying across the gym. Kids are being hit in the face. Kids are crying. Kids are planning attacks like army generals. It’s a war, but only it smells like sweat, plastic, and the fear of two dozen eight year olds. I’m on the front lines because grade three is also the last time I liked being the centre of attention. I’m dodging foam projectiles left and right, thinking I am smooth and graceful. Then, from the backlines, one of the boys yells out, “Hey fatty! move to the back, the bigger the target the easier to hit!” Up until that point, I had never really thought of myself as “fat” or a “fatty” or a “target big enough to get hit.” Sad and defeated, I move to the back of the line and watched the boys laugh together. They thought it was funny I was fat and were drunk with little seeds of toxic masculinity that was growing in their stomachs. From that point on, I began to think of myself as a “fat kid,” and I realized, the world did too.

I moved roughly eight or nine times before I was in grade seven, and each new school I fell into my roll as “new girl” and “new fat girl.” It became a routine. It was always the boys in the class who were first to point out my pre-adolescent rolls, and then the girls followed suit. I would get called names on the playground by the boys in the class, I would go to the teachers and tell them what the boys had said about me. Often, they would brush it off as a “boys will be boys” thing or, if I was really lucky, they’d tell me: “Oh, that means he likes you.” Around the time teachers started informing me that bullying by boys just meant they had a crush on you, was when I started developing crushes. This phenomenon of adults telling little girls that when a boy is mean, that means they actually like them, is nothing new. Ask any woman, and they will tell you at some point in their childhood a teacher, an aunty, cousin, mother, or some sort of authority figure, once was like, “Don’t worry that Tommy called you an ugly she-hippo and pushed you off the slide, dear, that just means he has a little crush on you.” It’s fucked. Yet as I grew from chubby child, to chubby teenager, to chubby adult, the echoing of men being shitty but that just means they like you followed and played a key role in my formative teen years… ok and my early twenties… ok and my mid-twenties.

Outside of my teenage hormone filled super crushes, I have had three big loves in my life. And all three of them were terrible. These are outside of people I have dated and slept with (sometimes they intersected, mostly they never did), these are the Big Three that I held a long burning flame for that was eventually snuffed out. The thing these men had in common, is that they were all very nice. I was so used to men treating me coldly or ignoring me all together, because, let’s be honest, most dudes do not give you the time of day unless they want to bone you. But the Big Three, I thought they were different. They weren’t the childhood boys from the playground calling me fat, they were nice! they talked to me! about books! and music! they became my friends. They became my close friends. They became loves of my life.

This isn’t about the “friend zone” this is about emotional labour

Every single one of the great unreciprocated loves I’ve had in my life were my best friends. Some of them knew I had feelings and some did not. They were self-described feminists, here to do their part to take on the patriarchy and help liberate the women. Or something like that. They read feminist theory, engaged in anti-oppressive politics, frequented radical spaces. These were the dudes, I thought, that could love a fat girl. They were nice guys. Just like I don’t exist outside of internalizing the male gaze these guys do not exist out of internalized toxic masculinity, but because they were nice and I loved them, I didn’t realize I took up a very typical socially prescribed role in their lives.

Now, before we get any further, I want to make it clear: people of all differing genders can all be friends with each other. I’m not saying that every person I’ve had feelings for is obligated to reciprocate romantic feelings back. I’m not saying that every person I pass on the street has to find me attractive, because attraction is complicated and highly subjective. What I am saying though, is that relationships don’t exist in a vacuum and desirability politics will always come back to bite you in the ass. Who we choose to love and who chooses to love us in return will always be inherently political. Now pile that on top of being a fat Metis woman, loving is never outside of colonial set boundaries and trying to love beyond all of this is a horrifically difficult act of revolution.

Loving these men was easy and terrible all at the same time, but I realized the hard way, that you can’t love someone into loving you the way you want them too. You can’t love someone so much and so hard that they realize they’ve been loving you the wrong way this whole time. It was complicated and messy, and often ended up with me five beers in sad texting my roommate telling her about all my feelings while we sat across the table from each other at the bar. There is an unbearable weight to loving someone, feeling inherently unlovable, but hyping yourself up because you think this nice guy is different than all the other guys. It’s not the other person’s fault you are putting all your eggs in their basket. And these people I’m writing about, they’re not “bad men.” They’re humans and I’ve seen them do a lot of work on themselves but unfortunately, undoing your internalized misogyny often doesn’t extend to really examining why you’re attracted to the people you’re attracted to. And really, I get it. I empathize with not wanting to do that work, because it means unraveling every bit of societal fabric you use to cover yourself up.

Long story short, I watched the Big Three loves of my life date skinny white women. I’m not joking, I’m not being hyperbolic, I’m very serious. All three of them. Once this happened after we had slept together and I told him that I had feelings. Like literally, they started dating two days later. When you’ve lived in a body like mine and you’ve grown up using humour as a coping mechanism, this is deeply funny. Trust me, you can laugh at it. I am. Now, I’m not delusional. I would not have harboured long-standing love for people if I didn’t think it was reciprocated. I was treated gently and tenderly by them. Sometimes we made out, hooked-up, and awkwardly cuddled in the morning after. There were moments made so confusing by the ever-blurring line of platonic and romantic that I would seek council from outside friends that were like, “Yeah my dude, it’s a go.” When all arrows are pointing to go, and you feel like maybe you can be loved enough to live outside your body for a minute, you throw yourself all in. Because, as a fat girl, you’re taught that moments where you are loved wholly and fully do not exist for you, so you need to learn how to love outside yourself. I found these nice boys to help me, love me, despite my body. I tasked these nice boys with an impossible mission that was destined for failure.

This doesn’t conclude in a nice neat package

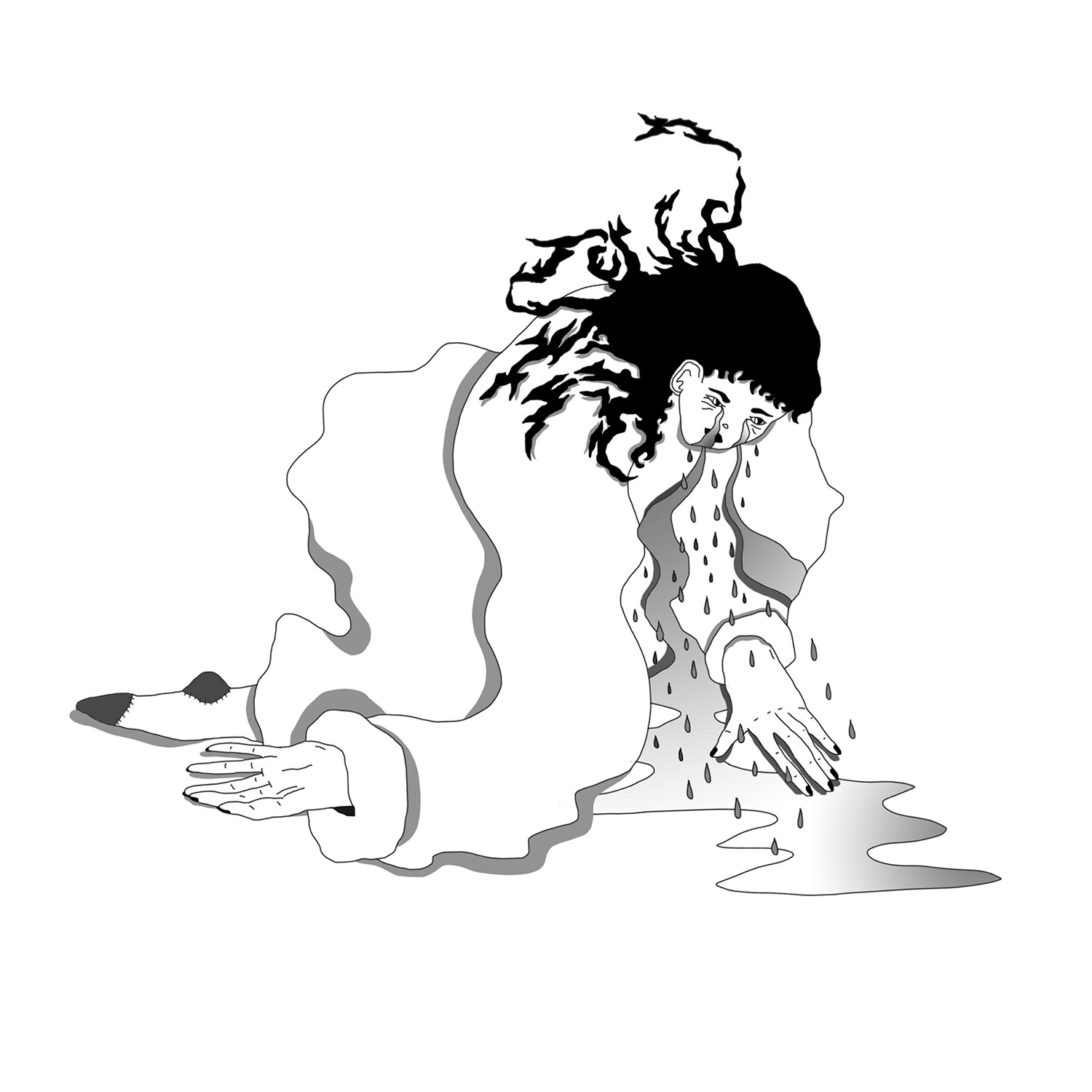

I’ve cried, a lot, about loves that were casualties in this war I’ve had against my body. I’ve cried about not being desirable enough for people to want to date me. I’ve cried about the differences in the ways my skinnier, more conventionally attractive friends, were treated nicer than I have been. I’ve cried because my skinnier friends were getting asked out and making out while I was still here, alone, with myself. I’ve shed so many tears about this, that I’ve developed a comfortable distance so far outside of myself that I sometimes feel like a voyeur looking through an uncovered window into someone else’s life.

The weeks leading up to my most recent heartbreak I was having nightmares about this person. He and I were fighting about mundane things, sometimes we were fighting about huge, very personal things. Often, we were just fighting because I think intrinsically, I knew something was off. I have always been told that our ancestors communicate with us through our dreams, and I laughed because I couldn’t imagine my great great great kokum warning me about a white boy. But I guess that’s probably not too far off the mark of a possibility. I had put a lot of hope into this situation and had declared this one the Last Time I Fall in Love. I’m really dramatic, sometimes (all the time). When the time came for the heartbreak to happen, I let it happen and didn’t really cry. Instead, I felt relieved. I felt like I could breathe again. I realized, that I had been holding my breath for so long, waiting, wishing, for an impossible situation to come to fruition. I had held out every hope for this one person to help me enter my own body again. This was a long lesson in learning that you can’t expect someone to just have the tools to save you because they’re nice and nice to you. You have all the tools you need already.

Hot take: decolonial love isn’t about how others love you

In 2012 interview for the Boston Review, author Junot Díaz, described a “certain kind of love” that could “liberate […] from that horrible legacy of colonial violence.” That “certain kind of love” he was talking about, was this concept of “decolonial love.” Decolonial love is a concept that has been taken up by many other authors who have felt the brunt of colonization. Anishinaabe writer Leanne Simpson came out with her pivotal collection of short stories entitled, Islands of Decolonial Love, in 2013. Most recently, in 2017, Anishinaabe-Metis writer and all around badass, Gwendolyn Benaway came out with her article, “Decolonial Love: A How-To Guide.” In her how-to guide, Benaway simply states:

“Love is constructed by whiteness and colonial narratives to be many things, but decolonial love is not a Katy Perry song. Love does not fix you, heal your past, resolve your insecurities, or lead you to violate your boundaries.”

Um, wow Gwen, why don’t you just @ me next time. Could it be that this whole time I was looking for love in the faces of these nice boys, looking for someone to love me despite my fatness, despite my colonial trauma, despite the laundry list of shitty things that have made me the anxious freak I am today, I was just playing into colonial narratives? Short answer: yes. Long answer: also, yes.

I have been spending time, since I was a teenager, trying to get others to love me into being a person. When I grew up, and started thinking through concepts of radical, decolonial love, I always hoped that someone would feel those things for me. I never stopped to think, that maybe, just maybe, you can’t find yourself in the body of someone else. You need to love yourself radically and wholly, outside of the boundaries colonization has built for you. Great epiphany I know, easier said than done. Loving yourself is simpler when you have someone else telling you why you should be loved, but when you live in a fat body, you are constantly living in a world that tells you exactly why you are not deserving of love or desire. If you’re a woman, you live in a world where your love and desire are tightly monitored and you’re told your emotions are not your own. Outside of calling it quits and becoming an old witchy lady that lives in a shack in the woods and scares the neighbourhood kids, I’m not sure what the answers are. How do you mitigate a society that continually calls you disgusting with the deep need to love yourself so you don’t turn into a shrivelled up, untouched raisin?

You just do it, at least, that’s what I’m starting to realize. You just have to take that big leap and say, “Sorry really nice white boy, but not today!” and put yourself first and learn how to love yourself deeply, and radically. The more I think through this the more I realize that radically loving yourself isn’t a destination. I can’t earn enough frequent flier miles on all my past mistakes in hopes that eventually I’ll accumulate enough to land me in the land of Self Actualization. The decoloniality of loving yourself enough is the actual journey you embark upon. Maybe this epiphany isn’t new and countless other chubber halfbreeds are sitting there mending their broken hearts with cans of Old Mill and cups of coffee, writing about how they think they’ve cracked the code. Or maybe it is. Either way, it’s new to me.

I’ve been reading a lot about genetic memories and intergenerational trauma. I’ve been thinking a lot about the dreams I have before bad things happen, and how my intuition is pretty much never wrong. I’ve been thinking about how maybe all of this is genetic memory. It’s my ancestors passed down traumas and insights that have lead me to live the complicated and messy life I have lived. It’s them, and their intrinsic teachings that already exist in my body, that have been teaching me all these lessons. Maybe, a part of decolonial love is finding a love outside of yourself that loves you through all the colonial trauma. But I think it’s more than that. Decolonial love is learning to love yourself so much so, that, when your future generations are sitting there, worried, anxious, and heartbroken, they can have the strength to pull themselves back up again and learn to love themselves: fully, wholly, and outside of another person’s existence. Maybe, just maybe, generations of the decolonial love passed down from our ancestors is that voice in the back of our head and the feeling in the pit of our stomachs telling us: “It’s going to be ok, you are enough.”

x

Samantha Nock is a Cree-Metis poet and writer from Dawson Creek, B.C.. Her family originates from Sakitawak or Ile-a-la-Crosse, Saskatchewan. She has been published in GUTS Magazine, Red Rising Magazine, Shameless Magazine, and Māmawi-ācimowak: Lit, Crit, and Art Literary Journal. She cares about radical decolonization, coffee, corgis, and her two cats, Betty and Jughead. You can find her tweeting at @sammymarie. More writing at halfbreedsreasoning.com.

- Kokum: Cree for Grandma

- Junot Díaz, “The Search for Decolonial Love: An Interview with Junot Díaz,” interview by Paula M. L. Moya, the Boston Review, June 26th, 2012, online. https://bostonreview.net/books-ideas/paula-ml-moya-decolonial-love-interview-junot-d%C3%ADaz

- Gwendolywn Benaway, “Decolonial Love: A How-To Guide,” Working It Out Together, https://workingitouttogether.com/content/decolonial-love-a-how-to-guide/