“This is a show about power.”

It is a white room that invites you in, and offers its various pieces to you as though showing you a secret. Milk crates, curtains and a faux-marble puppet smile at you, encouraging you to reflect on their function. While the objects themselves have a far more obvious function — pants, puppets, quilts — they have been edited by inheritance. Transformed by time, moved by legacy and new inhabitants.

The show in question, The Weight of Inheritance, exhibiting at Western Front from September to late October, is the most recent manifestation of artist Hazel Meyer’s ongoing project of the same name. “The Weight of Inheritance is me thinking through various kinds of legacies, and queer inheritance,” Meyer explains, “using my long-time fondness for Joyce Wieland as a starting point.”

“I first saw [Wieland’s] work when I was a pre-teen,” Meyer continues, “I saw her piece, Reason Over Passion, and it totally resonated with me […] I had never seen such a large work made with textiles before. And the humour! It was funny! It was unabashedly cute — there were hearts everywhere, and puffy letters, and while I couldn’t make total sense of what its meaning was at the time, I knew it was trying to communicate something to me — and using these motifs as a means towards that goal.”

In The Weight of Inheritance, Meyer uses her relationship to Wieland’s work as “a compass, and a pathfinder to other histories that aren’t given as much attention and care.” “My intention wasn’t to make a show ABOUT Joyce Wieland,” Meyer admits, “rather I wanted to see how I could think about legacy, power, inheritance etc…with Wieland and her marble as my starting point.”

The connection between Wieland and The Weight of Inheritance is not arbitrary. In fact, the project was born when Meyer was given slabs of marble that once belonged to the artist. In 2017, Meyer had done work based on Wieland’s Reason Over Passion which caught the eye of Jane Rowland — a woman who had moved into Wieland’s former home. Meyer and her partner Cait were given the opportunity to visit and tour the house. “On the second floor landing there were all these pieces of marble leaned up against the railing,” Meyer explains. The marble had belonged to Wieland, and Rowland offered it all to Meyer on the spot. So began The Weight of Inheritance.

When Meyer moved away from Toronto — two years after first meeting Rowland and a year following her passing — it was without the marble. She soon realized that it had become a symbol of her friendship to Rowland, “The kind of inheritance I was a part of was actually way more meaningful,” Meyer reflects. She adds, “I came to realize — and I know this sounds absurd — but that all marble is Joyce’s marble. Marble is older than any of us, it is of the earth, it’s shells that have been pressed together trillions of years ago, like who am I to own that?”

Meyer began exploring questions about inheritance through performance. Surrounded by various props based on objects found in Rowland and Wieland’s home, Meyer told versions of the story, “thinking about inheritance, class, queerness […] and what you pass on, especially without a biological inheritance of having children, how we leave things behind.” In one iteration of the performance Meyer picked up a heavy piece of marble, and invited audience members to come and hold it with her. “It was a way of suggesting we don’t do these things alone,” Meyer explains, “how do we come together and take care of people, thinking outside of a biological kind of family. […] How do we hold people’s pasts — if they want us to.” Meyer explains that in holding the marble, the audience was helping her hold its story.

From those first performances, the project developed into a scripted, three-person performance, featuring a puppet made to look like a chunk of marble, the Diana Ross song “It’s My House,” and a Shakespearean sonnet, amongst other things.

The exhibition that currently sits at Western Front was initially meant to be a series of performances developed and presented over the course of the exhibition, but the pandemic necessitated some flexibility and the performances became 2 person workshops between Meyer and filmmaker Alysha Seriani and writer s f ho. Even so, mobile milk crates and a pair of pants do what they can to conjure bodies in the space.

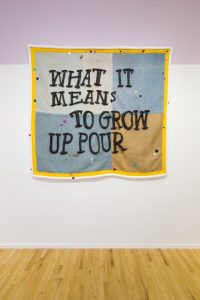

There are nods to Wieland throughout the room – in particular, a piece called Joyce Wieland’s Marble (2020 ) that looks like a cluster of slabs of marble, and a large quilt with the words “What It Means to Grow Up Pour” in puffy letters, an obvious reference to Wieland’s 1968 piece Reason Over Passion.

Hazel remembers attending a workshop during a social justice conference in her early twenties, in which participants were separated into different class brackets based on how they grew up. Participants were then asked to share a word that was typically used to describe people in their economic bracket. Hazel remembers being alone in the lowest bracket: “Of course I knew what they were looking for, and I was like, “I’m not giving you that, so I said, ‘intelligent.’” WHAT IT MEANS TO GROW UP POUR (after Reason Over Passion), is an echo of this, as Meyer reflects, “It’s not monolithic in any way. With this work I used the word POUR because I hope it might be misunderstood as a misspelling of POOR, which I thought might also make the person who thought this think about their assumptions, or experiences with regards to education and class.”

Across from What It Means to Grow Up Pour hangs a pair of purple leather pants. On the back of the pants, the words ABOUT POWER are stitched in white leather. “The pants could easily be found in a BDSM scene, the object of someone’s kink and desire… So thinking about power through desire, and various relationships with power […] a kind of positive radical desire.”

“This is an essay about power,” reads the first sentence of an article which hangs in miniature on the gallery wall beside What It Means to Grow Up Pour, aptly given the title, (This is an essay) ABOUT POWER, 2020. The text itself, “Power, Technology and the Phenomenology of Conventions: On Being Allergic to Onions,” is by Susan Leigh Star, and has traveled with Meyer for a while now. The Weight of Inheritance poses the question of “reengaging with structures and systems to make them work for those of us with less power than others.”

“Thinking about my own privilege as a white settler on these lands,” Meyer reflects, “and thinking back to that idea of ownership (with regards to Joyce’s marble and objects that are of this earth), I owe myself and the work, and really the world I move through, to constantly be thinking through how I benefit from certain structures, and how I can redirect that power, be an ally and stay true to what my politics are. The work about Wieland and her marble and Rowland gives a certain idiosyncratic scaffold to these ideas and moving through them. It feels fertile and generative.”

The Weight of Inheritance is indeed generative – of ideas, of questions, of conversation. It encourages us to think about legacies, inheritance, and power. “I like conjuring that word in this space because it feels like my first sentence of the exhibition.” Meyer shares, “This is a show about power — but it’s about so much more than power.”