Born in Singapore, to a Cantonese mother and a Hokkien father, meant that I grew up surrounded by a medley of flavours, dialects, traditions and ways of storytelling. From braving brutally bitter (yet nourishing) herbal Cantonese soups as a child, to helping my grandma make ba zhang (sticky rice dumplings) and popiah (a type of fresh spring roll) whenever she visited, food has always been the vessel through which I learned about my cultural identity. In Singapore, there are no heirlooms, nor genealogy books, and rarely did anyone know or speak of the past. After moving away from home and family, and settling as a guest in ‘Vancouver’, I have come to understand the importance of cooking Chinese food and holding fast to recipes and traditions fading along with the memories of my family’s matriarchs. When it comes to making Chinese food, all I had were meagre photos and that intuition chef Clarence Kwan speaks of in his new zine entitled Chinese Protest Recipes.

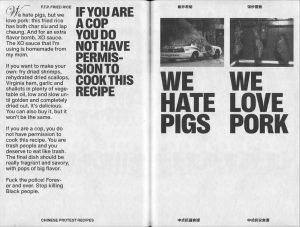

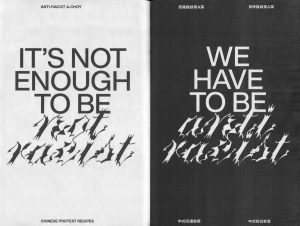

Chinese Protest Recipes (CPR) has struck a chord with many Chinese-Canadians, and newcomers like me. Throughout the zine, Clarence Kwan  (aka @thegodofcookery) calls us to respond to the pandemic, and the BLM movement through mobilizing the tools we have — our love for Chinese food and cooking — to resist white supremacy in our relationship to the food we choose to buy, eat and make. In centering Black lives and calling for collective action in the zine, Kwan pairs reminders of police brutality (thereby cheekily banning cops from cooking his recipes), statements of solidarity among BIPOC and personal anecdotes to each of the eight recipes he has curated. Each dish stands as a form of protest on its own. Among the generous peppering of black and white photos and understated yet beautiful typography, the mosaic of stories and recipes stand as stars of the show.

(aka @thegodofcookery) calls us to respond to the pandemic, and the BLM movement through mobilizing the tools we have — our love for Chinese food and cooking — to resist white supremacy in our relationship to the food we choose to buy, eat and make. In centering Black lives and calling for collective action in the zine, Kwan pairs reminders of police brutality (thereby cheekily banning cops from cooking his recipes), statements of solidarity among BIPOC and personal anecdotes to each of the eight recipes he has curated. Each dish stands as a form of protest on its own. Among the generous peppering of black and white photos and understated yet beautiful typography, the mosaic of stories and recipes stand as stars of the show.

CPR is not only a call to protest through cooking. It is also a love letter to his strong ties to Chinese restaurants and Chinatowns, in which he urges us to keep supporting local businesses reeling from the devastating effects of the pandemic and in Vancouver’s case, gentrification. Kwan drives home the idea that we must be active in our fight for anti-racism through food. This starts with reflecting on who we are, the way we acquire food, and claiming our cultural heritage by continuing to cook our food deemed “exotic” and “weird” by white culture, as well as keep up the work that still needs to be done in dismantling anti-Black sentiments within our families.

In centring food culture in the discussion of racial oppression, Kwan not only urges his readers to actively decolonize their relationship with food, but also shows how it could be a unifying process. In the zine, he writes “THE MORE WE EXPLORE AND SHINE A LIGHT ON BIPOC FOOD THE CLOSER WE GET TO A DEEPER UNDERSTANDING OF ONE ANOTHER”. He does his part in shining light on Chinese food, and shares the recipes with whoever is curious enough to try. It is only through sharing recipes with each other across communities, and coming together to prepare a meal, can these discussions on food happen.

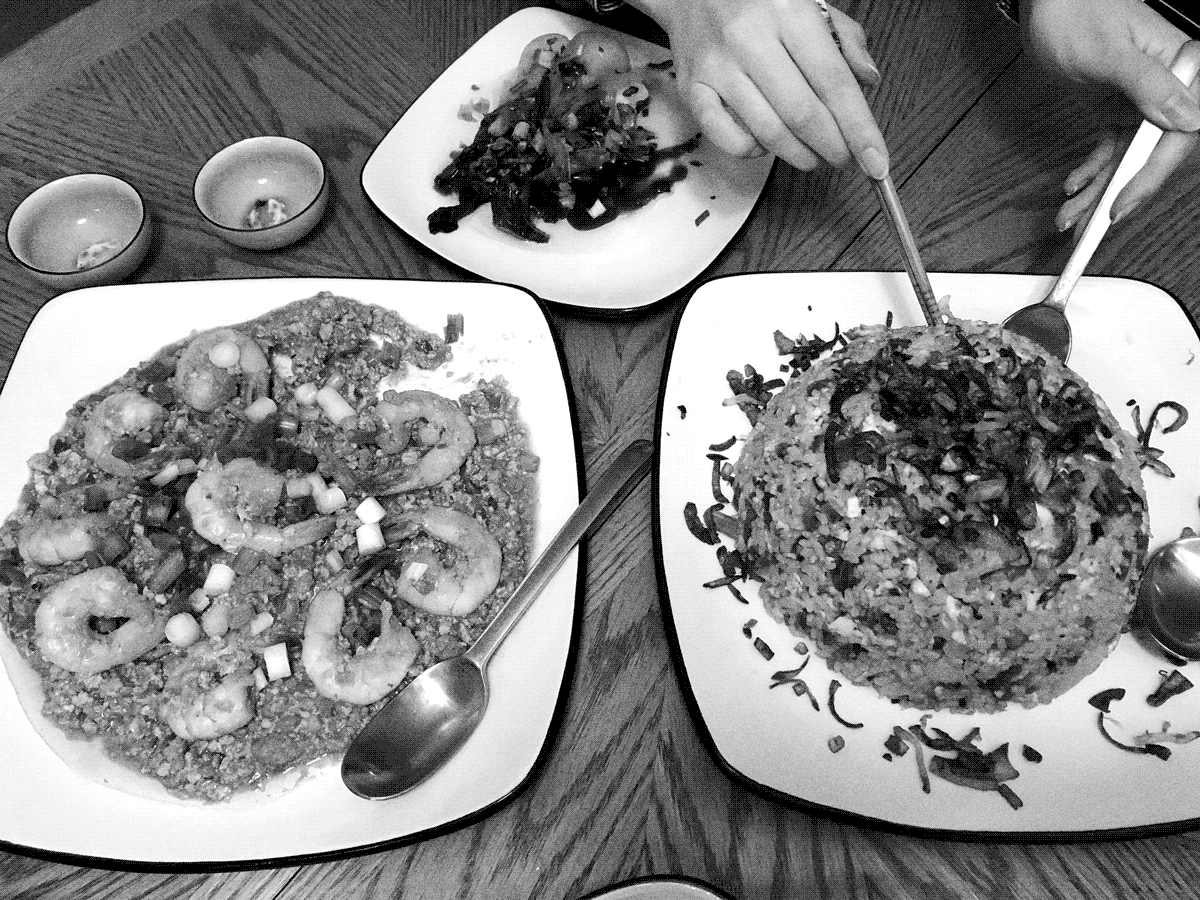

I would not be doing the zine justice if I did not try a few recipes myself. I invited a friend to join me in this process as she, being a first-generation Chinese-Canandian, shares my love of cooking Chinese food and preserving our cultural heritage. It was both our first times cooking such an elaborate meal apart from our families so we opted for familiar dishes that were not too ambitious — Shrimps in Lobster Sauce, F.T.P Fried Rice and A-choy doused in sesame oil and oyster sauce.

The recipes came with no measurements or handhold-y instructions, just simple descriptions inspired by traditions and oral history. We were forced to eyeball measurements and cook intuitively, tasting and adjusting along the way. It made me realize the potential for cooking to be so forgiving and fun, like an interpretive dance. It put a focus on making food which simply tasted good to me, and moved it away from mindlessly following a recipe. When we sat down to feast on the fruits of our labour, the first bite surprised us. At once, we sat back glowing with satisfaction at our abilities to cook something our grandmas would be proud of. Truly, delicious Chinese food is power in the hands of many.

A free digital copy of CPR is available on Kwan’s Instagram @thegodofcookery though he asks that you donate to support BLM or spread the word #ChineseProtestRecipes. You may also purchase a physical copy there.