Fear tends to expose the best and worst parts of what makes us human. Be it the greed that guides a hoarder’s cart at your local supermarket, to the uplifting sound of cheering against pots and pans. COVID-19 has given us a taste of what living in isolation means and what this might look like for people with chronic illness and disabilities — a reality that artist Olivia Dreisinger is quite familiar with.

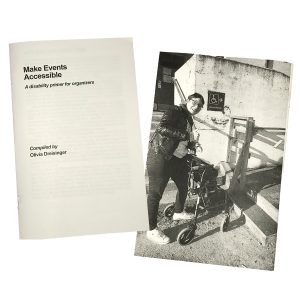

Olivia became chronically ill after a viral infection triggered an immune response that never went away. She describes herself as a “sick independent scholar specializing in all things disability,” and her work ranges from educational pamphlets like “Make Events Accessible,” to a documentary about a cosplaying service dog team, as well as interactive short stories, zines and animations. Speaking with Olivia, I wondered how she deals with isolation and pandemic as a chronically ill artist.

M: Tell us about your creative process, I understand it takes place inside mostly?

Oliva: Yeah, it’s actually never been that much of a problem for me, to be honest, because I’ve been intermittently sick since I was a kid. I have always been the home-dweller type. I think what you’ll see in the work that I do now is I’ve always put what I’ve learned from my own isolation into my creative and academic practices. My work has always built accessibility into it and, because of my illnesses, I need to work slowly. I need to sleep a lot and I need to stay home, or at least, really close by in case I need to return home to rest. And so, I think the medium has just grown out of that. I write a lot. I taught myself how to make 3D animations just so I could sit at home and be very physically still while working. I used to also  take photographs when I was more able-bodied, but I’ve had to re-evaluate how I do that now. I’m still working on how to make photography work with my body. More recently, I’ve been working with plants. I’ve been making herbal salves and teas and vinegars to support my body through illness. I’m also trying to figure out if there is a way to bring that into my creative practices. You have to be really resourceful, I think, when you work from home.

take photographs when I was more able-bodied, but I’ve had to re-evaluate how I do that now. I’m still working on how to make photography work with my body. More recently, I’ve been working with plants. I’ve been making herbal salves and teas and vinegars to support my body through illness. I’m also trying to figure out if there is a way to bring that into my creative practices. You have to be really resourceful, I think, when you work from home.

There’s a constant unpredictability and spontaneity spurred by illness that Olivia has allowed to shape the space her art inhabits. I imagine it kind of

wrapping around her computer, a viney growth that bolsters a certain strength around her pieces. The necessity for resourcefulness has sprouted a freedom of versatility in her crafts. This similar source of strength can be felt from the story told in her documentary, “Handler is Crazy,” which can be streamed on Youtube.

M: You received a grant to create the documentary “Handler Is Crazy.” Would you like to talk about that?

Olivia: Yeah, sure. So, I was really fortunate to receive a grant through the Canada Council for the Arts to make a documentary and it was my first time ever receiving a grant. The documentary is about a woman named Koyote Moon and her service dog Banner. Banner is a medical and psychiatric dog, who also cosplays, which is why I was initially interested in making a documentary about Koyote and her life. Banner would dress up as characters that had similar disabilities or conditions to Koyote [and cosplaying] became this interesting kind of advocacy thing, beyond Banner’s regular service dog tasks. Service dog knowledge is, I think, pretty limited in Canada, which was another reason why I wanted to make a documentary about this particular team. I think the definitions around service dogs are growing and service dogs are not just for blind people anymore.

A large part of Olivia’s art is providing educational resources that create dialogue on how to improve the emotional, physical and financial wellbeing of people with disabilities through sharing sick and disabled experience in zines, digital rendered videos and print-at-home pamphlets. Her zines range from the “little book of herbal vinegars for sober, sensitive, or alcohol intolerant folks” to “what is a service dog? 2-in-1 booklet providing information for the general public and prospective handlers.” She says she’s jumped to zines now because zine culture is all about low costs and circulating radical stories and media. They’re easy to convey information through, and most importantly, she says, they don’t have to be perfect. Olivia also has a new zine project, tentatively titled Eco-Crips Against Toxic Ecologies, which aims to expose toxic systems like ableism, speciesism and environmental injustices. Even though these topics might sound daunting to someone who hasn’t ever participated in conversations within accessibility politics, Olivia explains to me what ends up being a common theme throughout her interests — to make things simple. And, sometimes, a little laughter is the simplest remedy to help get the point across.

M: Can you speak to how you balance the gravity of these things with a palpable sense of lightness and humour? As in the “Make Events Accessible” zine, which features a photograph of an incorrectly marked accessible entrance?

Olivia: I don’t know if it’s funny to nondisabled people — but it’s funny to disabled people because it’s kind of like, oh, of course, you know, like there’s a step. You were so close to making the ramp accessible, but there’s a step! So therefore it’s not accessible, you know? It’s kind of funny how people don’t really think about access very well, or they put in like, 90 percent effort and fail at the other 10 percent.

Olivia also explains how the spectrum of disability leaves room for the creative process to find ways of adapting and accommodating access needs that can be exploratory and fun.

Olivia: It can be fun and also humorous, you know, like having these random, clashing, access needs. And like you said, there’s a lot of humour in the work that I do. I think when you live in an unruly body — a sick body — you don’t take things for granted because you have to scale back or limit the things you do. You start interacting with systems, other people, and your own body in ways that I don’t think non-disabled people do. There’s a lot of joy and a lot of pleasure, ironically enough, in being sick and ill.

This deep sense of gratitude, pleasure and joy, garnered from tasks like making a trip to her local supermarket is something Olivia says are routines she misses now within the pandemic. The world has changed drastically with the spread of COVID-19, and the risk for someone chronically ill walking to get groceries is simply not worth taking.

Sometimes art serves as an eruption of feeling, other times it lingers between survival and hope. Sometimes it is meant to inspire — other times to soothe. Olivia told me about how she had begun foraging for poplar buds to make anti-inflammatory ointments to help alleviate pain. Crafting these herbal elixirs and tinctures are a new way she’s begun to find ease.

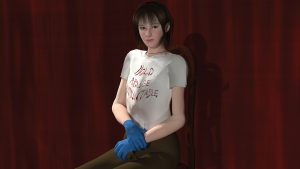

Since we weren’t able to carry out a photo-shoot for this piece, a precautionary measure due to COVID-19, Olivia was gracious enough to accommodate by creating a 3D self-portrait. Using her art as a means for accommodation was actually her entrance into digital rendering, and it all began during her masters program at McGill.

M: Why does 3D Animation speak to you rather than drawing?

Olivia: I actually taught myself how to do animation during my thesis. That was when I was getting really sick, and I was almost failing out of McGill. In order to access disability services on campus, you had to have a definite diagnosis and I didn’t have that on hand. And so, without a definite diagnosis, professors will fail you [for not] showing up to class. Animation kind of came out as a way to survive. I opted to do a creative thesis, to make a video essay, and it was a way to build accessibility and survival into my practice. I think it also kind of substitutes for the scaling back of my photography practice — I can kind of transplant my photography practice into this 3D landscape and have that work for my body. Another thing to note is that the 3D program that I’m working in is free, so it’s financially accessible and there are a lot of free models to use. People are collectively doing this labour, offering resources for free in order to support creatives. I think that’s also why I became really interested in [3D animation], just to see how people were using their time and labour, and putting it into the world.

We spoke more on the solidarity within the disability community, and what it looks like during the pandemic. Another space which displays this collectivity and built-in accessibility, is the fan-fic community, which also inspires Olivia’s work.

M: What brings these communities together and how has this collective action changed in the midst of the pandemic?

Olivia: So, I think fan-fiction pairs really well with the 3D universe that I work in because they have these built-in access interests. Now that I’m moving towards more academic terrains, or with the Make Events Accessible zine, for instance, disability representation has become really important to me. I also recognize that I come from a very specific point of view with my own health, and I can’t know everything about other disabilities. So, you know, just talk to other people who have different disabilities, and make connections with them, and hope that they offer their valuable knowledge to you so that you can also represent them accurately so that people also start caring about them and what they need. I think that’s also, like, the academic in me — I want to know it all. I want to know inherently in my body, all of the disability experiences, but I just can’t. *laughs* With the fan-fiction community, it’s the same thing. It’s like everyone is contributing to the 3D universe. Everyone’s contributing within the disability community. If you look now at disability Twitter, or disability Instagram, with the pandemic, everyone is trying to provide care and mutual aid to each other because everyone’s pretty scared right now. Going back to the reality of COVID-19, a lot of people’s really important medical appointments are being canceled, or they’re scared to go to the hospital, or they already have run out of nitrile gloves and hand sanitizer. So, you know, everyone’s kind of sharing what they can. I shared my hand sanitizer with my neighbor, who is also sick. We’ve been dropping off care packages outside each other’s doors. I’m going to be sewing fabric masks later today and kind of helping distribute them. So, yeah, you can’t really work in disability in an isolated bubble. You need to be caring and working with everyone else in the community.

M: Is there anything else that comes to mind that we haven’t touched on?

Olivia: I mean, I have one other thing to say, and it’s funny because with this quarantine, it’s actually been the most social I’ve ever been online. Now all of these non-disabled people are coming up with creative ways to interact with each other online and I feel like pre-pandemic no one would have extended that gesture to people who are in isolation all the time anyways. It’s been weird because people are now making an effort to make socializing accessible to me. I hope that once quarantine lifts, people start caring about the disability community all year round.

The comradery felt within the accessibility community is contagious, and Olivia Dreisinger’s art demonstrates the power found within uncertainty. The versatility of her work is an ode to endurance and gives us the opportunity to rethink our pain and forage pleasure from places we never thought we’d be in. But beyond indulgence, her art seeks to expose the diverse ways we interact within the sick and disabled experience. It also demands that the crucial infrastructures created under the pandemic which serve these experiences do not end with the virus. Because after it passes, there will be problems which cannot be solved by vaccines — those which require our continuous vigilance. Some of us are simply visitors to the troubles of our time in the pandemic.

You can find all of Olivia’s work on her website.

Her instagram is @pookie_croissant and you can watch her documentary ‘Handler is Crazy’ here. For a copy of her zines, you can email her at: oliviadreisinger@gmail.com