The hyperpersonal and the generally relatable are a dialectic that Hue Nguyen expertly balances. Hue is a multidisciplinary artist (and a horse) practicing in Vancouver. With clear and precise compositions, lines and palettes, they needle the connective tissue of their experiences and reflections together with theory and intuition.

Nguyen sees their work as an extension of themselves. They began to work seriously on their art practice in 2017, which was a particularly difficult year for them. They returned to a childhood hobby — drawing — for comfort. “It was healing to put all these drawings out and really put myself into it,” Nguyen explains. “It was a great way to reflect on my mental health while still being creative.” Their work is an abstraction of their experience. It conveys what they feel less able to articulate in words.

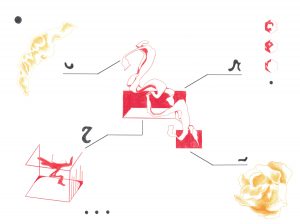

Approaching each piece from intuition rather than a visual plan, they are a process-driven artist. For each work, they first write a poem and then visually abstract it. To them, these poems act as scripts for an emotional timeline wherein “it’s all about how the reader will feel while going through it. That’s what I’m trying to communicate rather than some storyline or actual narrative.”

This intuition, with a basis in Nguyen’s own experiences and management of them, binds the content with form. Their pieces have a feeling of being necessarily the way that they are. That line is there because it has to be, that juxtaposition of texture is there because it’s what needs to have happened. There is something deliberate in the way their work unfolds — and that deliberateness comes from the artist’s honest, self-reflection. Of being a person. Herein, Hue’s contradictions are cohesive, their personhood feels inevitable. Being honest about it lends their work cohesion and inevitability.

Nguyen actively toes the line between the hyperpersonal and broadly accessible, and that is what makes their work so resonant. It’s hyperspecificity peeks at relatability. “I like to make work about myself, but in a way that can reach a further audience,” they explain. “I want it to be personal, but not too personal, just enough that it’s general enough to have a relation to the audience.” Being honest about their personal idiosynchronicities — resulting from their experiences as a first generation immigrant, a Vietnamese-Canadian, a non-binary person, an artist, an (in their own words) egg-head — simultaneously reveals to their audience their own specificities, cohesiveness, and inevitiabilities.

While Nguyen’s return to visual art has been their recent focus — and catharsis — they are multitalented, having also experience in film, soft sculpture, and textiles. They admit to having “a strange relationship with physical touch and bodies,” and moving into this third dimension is particularly exciting for them being able to “actually get to do it with [their] own body, and feel it within [their] hands and feel it between [their] fingers.” This sentiment is aligned with their approach to their 2D practice as well, because they prioritize physical, tangible work. “I’m a firm believer in paper. Anything of my own that I have the control to publish I want to print physically.”

With that physicality, they have started to explore the physical world as another point of abstraction. Their 2018 publication “Red Rainbow” is an exploration of their experience on the antipsychotic Risperidone — a medication both they and their mother were prescribed. They wanted to understand how it was affecting them and translate that experience visually. To do this, they referenced images of relevant parts of the brain, abstracting the diagrams to ensure they are “taken in a way that [they’re] owning.” From this springboard, Nguyen has steadily incorporated more science into their content, “I’m interested in neuroscience because of its relation to mental health. I was interested in the brain and the body. My work is moving towards the intersection of philosophy and neuroscience, as well language and semiotics.” Importantly, they draw connections between science, philosophy and their own human experience. “Right now I’m really researching how starfish operate, and relating myself back to that in a human sense.”

Their appreciation of the sciences — and biology in particular — as a poetic field compliments their return to visual art. It was a field they were interested in in their youth and are returning to as a means of contextualizing their adult experience. In this vein, their current research links starfish morphology and psychoanalysis. To Nguyen it explores “the idea of being past the chaotic phase and what happens now in terms of how I understand myself as an individual.” Approaching their practice both from a place of extensive research, and inuiting their emotional response, contextualizes their experiences — it informs the precision and intention of their work.

This braiding of research with intuition also makes Nguyen’s work appealing to a broad range of perspectives — some to whom STEM feels more comfortable, and some who gravitate more towards the emotional tug of the work.

Upon researching Hue Nguyen, one thing that consistently appears is their identification as a horse, or horse child; as they say: “I’m a horse, get over it.” Across artist statements, across publishers, across years, Nguyen has consistently made space for their connection to horses. Never having been obsessed with horses as a child, Nguyen “started to fall in love with horses when […] going through a rough phase and living with a friend who had a big ranch. The horses were very calming, just big and lumbering.” Nguyen’s connection to horses reflects the steady deliberateness of their work. The playful openness with which they pull inspiration from multiple fields.

Their breadth of inspirations brace their exploration of agency — and this is the crux of their practice. “Agency is such a big thing for me. Some of my work is about how the body is reacting [to being contained] and putting that in a framework and then having the audience member react to that. It’s about how my body is feeling and what it is,” Nguyen explains. Agency is a thread connecting almost every element of their work, from neuroscience, as in how, as Hue illuminates, “self-inflicted pain is a strange form of agency because it’s all on your own. How the body and pain work together is [itself] a form of agency,” to enacting belonging. Nguyen has reclaimed the use of their first name, Hue, as another form of agency and as “an idea of creating [an] agency with individuals,” this is their way of situating themselves in their community. Though they are Vietnamese, they pointed out that they “always felt like [they] didn’t belong in that community growing up.” Returning to their first name, enacting that agency, allows them and other first generations to ”become part of this community where you don’t necessarily feel like you belong.”

This agency is also enacted in their process. Their work being this extension of themselves means they can control how they are perceived. And that sense of control is also present in how they arrange their compositions, as they say, “my work is an extension of myself, and there’s so much room to breathe because I am such a reserved individual. It’s really important for me to have that reservation and delicateness in there.”

The intention of this technique is also present in their textural pieces, or lack thereof. To Nguyen, “the textured portions are the parts of myself that are actually speaking and articulating in some kind of way.” The pieces speak and breathe for them.

Nguyen’s work is an incredible example of an artist using their practice to interrogate their experiences — and reactions to those experiences. This balance of dichotomies — the personal and the general, the scientific and the poetic, the researched and intuitive — not only lends Ngyuen’s work a richness beyond the richness of their own personhood, but also an incredible range of entry-points into what is, necessarily, a very personal body of work.