With Time in Our Hands

All This Time is an ongoing online exhibition curated by Number 3 Gallery; a mobile curatorial project centering emerging contemporary artists and spaces.

As a response to the abrupt cultural changes and new circumstances of this spring, #3 invited participants of any artistic genre to submit work that was not immediately ‘art’ related, but in distinct ways could contribute to discourses around legitimacy, value and productivity in cultural landscapes of capitalist, patriarchal and ableist behavioral norms. Topics which are not only symptomatic of the current moment, but have become even more evident and urgent in light of recent events.

Setting out as an exploration of the ways in which we adapt and respond to moments of crisis, the exhibition provides a digital frame for rethinking embodiment, materiality, and temporality to discover healthier time orientations. After all, “crisis” is nothing new. Health crises, climate crisis and economic crisis have all long formed part of our lives. What is extraordinary about the current moment then, might be that we no longer will accept the normalcy of emergency.

Presented as a curatorial project in a blog-style format, the exhibition creates new forms of kinship through and beyond online presence. All This Time is not only a documentation and archive of our daily resistance to surrendering to “Gore Capitalism”, but an example of our interconnectedness and affective bonds to nonhuman forces. It is no longer enough to demystify the world. In order to create images of hopeful futures, we have to actively re-enchant the world. In this context, technology becomes not only a last resort, but a tool for social change.

On a digital wallpaper more blue than the sky, both #3 and the artists use this expansive realm to reimagine a vibrant future of human and non-human bodies. In a time where life on-screen often has us feeling more embodied and connected while the real world increasingly distances us from our bodies and sense of reality, All This Time subtly reminds the viewer that it’s not only what we make of objects — but what they make of us. It’s the ability of inanimate things to have material effects on our lives, pulling us in and out of our own materiality — Like Donna Haraway said; Why should our bodies end at the skin?

Stepping Outside The White Cube

#3’s curatorial approach to online exhibitions centers the need for growing sustainable systems of exchange — recrafting definitions of institutional and human bodies, both online and off. The result is at once a quiet, introspective experience of slowing down and withdrawing, as well as an urgent institutional critique, calling for action.

Nellie Stark, one of the participating artists, demonstrates in a video piece the functionality of a reversible top she made as a result of finally having time to familiarize herself with a sewing machine. The text included underneath reads: “Turns out I have endless patience for intricate embroidery, but none for using a machine to sew a straight line.” As a non-binary person I’ve always found it difficult to follow straight lines. Maybe it’s because the perfectly aligned lines of machines and of capitalist society are out of tune with the movements of our bodies. Is straightness an ideal only because it is unreachable? Perhaps every person has their own temporal rhythm to follow. One that is as intricate as embroidery on a shirt.

All this time makes space to think outside the white walls of the gallery, effectively destabilizing normalized ideas of (re)production, value, and legitimacy. It seems to ask us; should growth and linear progression still be ideals we live by? And at the expense of whose diminishment or exclusion? Can we embrace slowness as a political act? Practicing institutional slowness requires abandoning the idea of the white cube as a timeless place — free of social or political context. To bring value back into daily life and lived experience, as All This Time challenges the assumption of neutrality and timelessness within online and offline institutions. This is a powerful way of restructuring the architecture of the white cube that separates artistic value from the presumed outside political and social sphere.

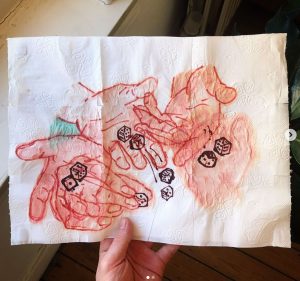

There is nothing innate about value. It has no essence, and is forged by the ideals of a specific time and place. Some objects acquire more value with time, like archeological artifacts, while others, such as an old TV, quickly lose value and slide into the category of trash. John Padrino’s illustrations on toilet paper —a commodity which during the pandemic gained an almost incomparable value — exemplifies this logic. Value seems to be given to whatever is in shortage, whatever is running out. The work forces the viewer to consider their own position in the current landscape of consumer capitalism — buying into the fear of scarcity. Just imagine the gallery of the future in a far distant galaxy wherein the cyborg visitors admiring Padrino’s work wonder why on earth human beings panicked at the threat of a lack of toilet paper, but not at the threat of climate change.

Leslie Leong’s work leaves us to reflect on how some human traces change landscapes forever. The video of the melting permafrost becomes evidence of the immediacy of climate change and the precariousness of communities who might not have the privilege of time as temperatures continue to rise and their lands disappear. Leong’s works shows us the mechanics of time and how it works as an unequally distributed social currency. It invites us to gain new understandings of the interwovenness of human and non-human forces, and the damaging effects of temporal oppression.

Re-crafting Technology

Gloria Avgust’s work; a Heron’s fountain made from rubber tubes and SPA water bottles placed on a steel ladder brings back memories of 4th grade science projects. The feeling of achievement watching the modest squirt of water somehow not giving in to gravity blurred distinctions between science and magic — the fountain is simple, yet as mesmerizing as childhood itself. As kids we experience the world as enchanted. We didn’t feel the need to understand its magic as much as the need of simply experiencing it. What is the difference between science and magic, really? Isn’t magic just a word used for technologies we don’t understand?

The works in All This Time reframe the term ‘technology”. They carefully consider more embodied and intimate forms of technologies, like the technology of sound, language, and time. Technology and the future often appear in the same discourse, as if technology equals futurity. Technology is imagined through the image of computers, artificial intelligence and cyborgs. This imaginary detaches technology from the past and the etymology of the term, leading back to the Ancient Greek word “tekhnē” referring to ‘art’ and ‘craft’. The works reinsert art and craft into the meaning of technology suggesting that technology is the everyday magic we make with our two hands.

A fountain is just one kind of technology. Historically, fountains began as purely functional, being important sources of drinking water. However, they later on gained decorative value, becoming urban landmarks that showcased the wealth of cities. The circular flow of a fountain that is unaffected by the lack of an audience or human interference brings time into the visible realm reassuring us that time still moves, even in a global moment characterized by the feeling of loss of time. The flow of water is like the flow of time. Waves are like memories slowly bouncing back in a circular movement, like recurrences of history repeating itself. Why do we feel the need to create, to make and reinvent things, especially in a time of crisis? Perhaps Avgust’s revisiting of ancient fountains is a way of refusing to forget how old crafts have always been embedded in modern technologies, and how the use of these now seemingly obsolete technologies help us move forward as we invent new ones.

We Touch Screens and Technology Touches Us Back

When I take a break from social media I worry about missing out. When I spend all day on social media, I worry about missing out. Sometimes after falling deep into an Instagram wormhole, scrolling until my wrist hurts, I am convinced this object has become an extension of my hand. A  prosthesis of its own smooth and glimmering skin. Bodies extend themselves through objects and we adjust to their presence to exist in synthesis.

prosthesis of its own smooth and glimmering skin. Bodies extend themselves through objects and we adjust to their presence to exist in synthesis.

What happens when technology seems to know more about us than ourselves? Marika Vandekraat’s work of a screenshot Duolingo lesson, juxtaposed with a digital collage of Iphone images, reconfigures the notion of inanimate matter while considering the growing extent of surveillance systems and autonomous machines. The images of everyday objects now rearranged and detached from chronological order suddenly appear foreign. As objects are removed from their ordinary context they acquire life and symbolic value beyond their mere function. Duolingo’s daily reminders become a disciplinary and regulatory force upon the malleable body. These notifications provide a sense of structure and routine by telling us, ‘it’s time for your daily lesson’, while further proving that in a time when institutions fail to operate as they were supposed to, we tend to find ways to continue their work that has already become so ingrained in us.

As the translated words on the screen reads: ‘the artist keeps hoping’, we are reminded of how easily computers read our mind through algorithms detecting and further shaping our behavioral norms. We now touch screens more frequently than we touch skin. Not only as passive spectators, but as users we are forced to acknowledge the affective bonds and connections we make with inanimate things as we tell them secrets that we might never say out loud, but reveal by the subtle movements of our fingers passing over a screen.

Time Orientations of Healing: Seeing The Horizon

The works in All This Time seem to ask; how do we reclaim time, when time was never in our favour to begin with? It is then more a question of (re)encountering healthier time-orientations, abandoning the universal and linear perception of time so deeply embedded in Western culture, than “getting back to normal”. There is feedback between the past and present and the echoes of the past always find their way into our lives.

Doenja Oogjes, a design researcher working within speculative design, found herself invested in watercolor painting while experiencing the sudden time on her hands. The blue and red patterns mirror the slow repetitive movement of the brush shaping them. Doenja herself explains the calming feeling of repeating the same movement, almost as if experiencing time folding in on itself, layer upon layer, bending and twisting. The soft U-shaped strokes turning into triangular shapes then becoming sharper Z-shaped figures are perhaps a slow countermove to consumer capitalism and its demand of constant progress and efficiency. The work visualises how patterns — in paintings or in society — are never the product of an immediate and singular event. Rather they are shaped by recurring movements. The self-regulating experience of repetitive motion is not about controlling time, but rather to tune into its shape-shifting materiality. Everything exists on its own timeline, a line which is not a line at all, but rather, slow bended strokes or curves. The paintings somehow echo patterns created by weaving and I am reminded that the world’s first computer was, in fact, a loom. Another traditional craft, or technology, if you will.

The folds and bends of Oogjes watercolour paintings are not unlike the curves and folds sealing homemade dumplings. Yujin Kim’s work presents an exploration of heritage and the time traveling technologies that allow us to feel at home. Preparing a home cooked meal requires the same amount of skill and attention to detail used in the making of a sculpture or painting. The work ascribes value to embodied and sensory experiences  allowing them to become sources of knowledge and storytelling. In a future oriented society, looking back and giving oneself time to repeat gestures of undersung practices is a subversive act.

allowing them to become sources of knowledge and storytelling. In a future oriented society, looking back and giving oneself time to repeat gestures of undersung practices is a subversive act.

All This Time allows the visitor to think beyond limits of the presumed lifeless blue-screen, while recognizing the challenges of online existence. Centering works that imagine new spatio-temporalities of being and becoming in a time marked by loss of linearity and coherence, the exhibition provides a glimpse of a future that arrives at, and departs from, the subtle force of everyday lived experience. In an unsustainable environment of constant rush, to slow down and make time for repetition, stillness and ritual might be an act of resilience that counters the imposed linear time.

The artists in All This Time use technology as a means, rather than end, allowing new forms of kinship and gathering to be imaged and effectively enter the digital and daily realm. After all, pivotal change has never been a singular event in time. The revolutionary potential of the everyday is in the simple act of taking our time. All This Time is a portal inviting us to reconsider the boundaries of our own bodies, acknowledging how human existence exceeds the flesh. Time is a substance as malleable as clay in our hands. With all this time on our hands just imagine what we could build.