“We need you to come to the table,” is the message that Dalya Israel, Manager of Victim Services and Outreach Programs at WAVAW, has for men and boys. In a room where survivors of sexual assault can access counselling, legal assistance and other support services, Discorder sits with Dalya and Sonmin Bong, Volunteer and Educational Outreach Coordinator, to discuss the role that men should hold in today’s movement to end sexualized violence. “We know that the majority of perpetrators [of sexual assault] are men,” says Sonmin. “Yes, they’re a part of the problem, but they can be part of the solution, [which] leads us to the natural conclusion that it is absolutely necessary to work with them and educate them.”

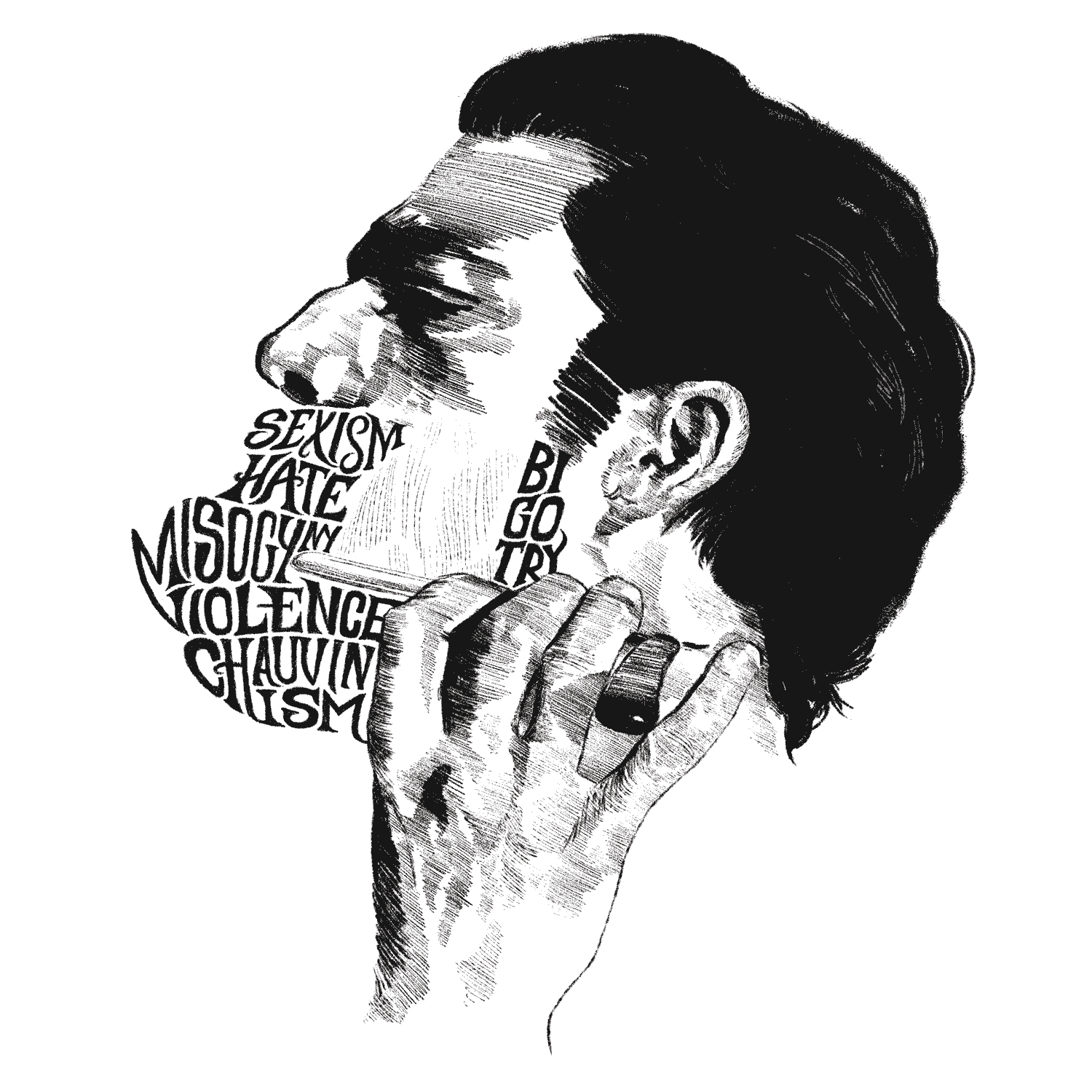

According to Dalya and Sonmin, one of the major factors in the frequency of sexual assault is the encouragement of “toxic masculinity,” an exaggerated form of masculinity with excess arrogance, aggressiveness, stoicism and hypersexuality. Toxic masculinity glorifies sex and ego. It prompts men to value the conquest of a sexual encounter over the consent of the individual with whom they are having sex. To many perpetrators, the conquest is justification for a sexual assault.

Dalya and Sonmin emphasize, however, that toxic masculinity not only harms the targets of men, but also the men themselves. “We know that [traits of toxic masculinity] don’t even feel authentic to so many people,” says Sonmin. “They’re like, ‘Actually these are not really parts of myself that I want to embrace.’” Yet, Sonmin explains that patriarchy “continues to reinforce the idea that if you’re not living up to these ideals of toxic masculinity, then you are […] the opposite, which is feminine.” What Sonmin refers to as the “hatred of femininity” in our patriarchal society means that in certain circles, there are social consequences for men who are perceived to display femininity by refusing to engage in toxic masculinity. Thus, toxic masculinity can manifest from deep insecurity and fear.

The most damaging trait of toxic masculinity is when men adopt emotional detachment. By designating emotional sensitivity as a feminine trait, Sonmin explains that toxic masculinity makes men feel that they “can’t access their own emotions.” Dalya believes the fact that “young men are experiencing depression and anxiety at ridiculous rates” can be attributed to the suppression of their emotions.

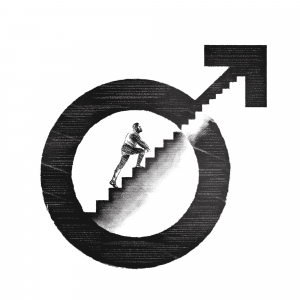

It is evident that toxic masculinity needs to end before any significant progress can be made in reducing acts of sexual assault perpetrated by men. An alternative masculinity has come to be known in feminist circles as “healthier masculinity.” However, Dalya and Sonmin, even as experts on feminism, refuse to comment on what they think the traits of healthier masculinity should be. “We want to give that back to men to figure out,” Dalya says. “The feminist movement has done so much already to bring awareness to how toxic masculinity plays out in our society,” comments Sonmin, and Dalya adds, “Now it’s [men’s] turn.”

Aside from the distribution of emotional labour, Sonmin and Dalya believe that women and non-binary people should keep out of defining healthier masculinity as a matter of principle. “Let us not be the people who flip the script and say [to men], ‘Now we’re going to tell you how you need to behave,”’ Dalya says.

Dalya and Sonmin admit that the task of eradicating toxic masculinity is a difficult one, as toxic masculine traits are often subtle and difficult to detect. “Sometimes I don’t know if we can really separate healthy masculinity and toxic masculinity, or distinguish masculinity from toxic masculinity like that,” explains Sonmin. They suggest that instead of focusing on the specific traits through which toxic masculinity is expressed, men should take a more macro approach, searching for and addressing the thought patterns from which those traits stem. Sonmin gives an example: “Feeling entitled to people’s bodies. […] Like, where’s that [feeling] coming from?”

Men must also learn to intervene when they find themselves in toxic situations, especially in circumstances where they witness sexual assault or harassment. “We have such a huge influence on each other,” says Sonmin. She explains that a comment from one man to another, such as “‘Hey, the way you touched your friend at the party, you really should not do that,”’ can be effective in prompting someone to rethink their sexual conduct, thereby dissuading future assaults.

Since 2018, WAVAW has offered support services to sexual assault survivors of marginalized genders, for whom sexual assault is an impact of systemic, gendered oppression. This includes all women, Two Spirit, trans (including trans men), non-binary and gender-diverse survivors. For men seeking more information on how to disengage from toxic masculinity, WAVAW’s website offers an ideal starting point. The page “What Men and Boys Can Do” contains videos and links to blog posts addressing how toxic masculinity harms men and perpetuates rape culture, as well as links to the websites of men’s organizations that address healthier masculinity.

Dalya and Sonmin are confident that men are willing and able to eliminate toxic masculinity, but they are realistic in predicting that a mainstream healthier masculinity movement and a commitment to end sexual assault will not pop up overnight. “We all have to dedicate ourselves to the reality that men are not perfect,” says Dalya. She explains that before our presently patriarchal society can adopt feminist causes, men will have to “heal […] and to want restoration.” This will take time, self-reflection and hard work on their part, as well as “a lot of courage,” Dalya adds.

X

Visit wavaw.ca for more information about WAVAW services and links to additional resources. If you frequent UBC-Vancouver, the AMS Sexual Assault Support Centre (SASC) also offers resources and workshops related to sexual violence, along with a Healthier Masculinity program. Visit amssasc.ca for more information.