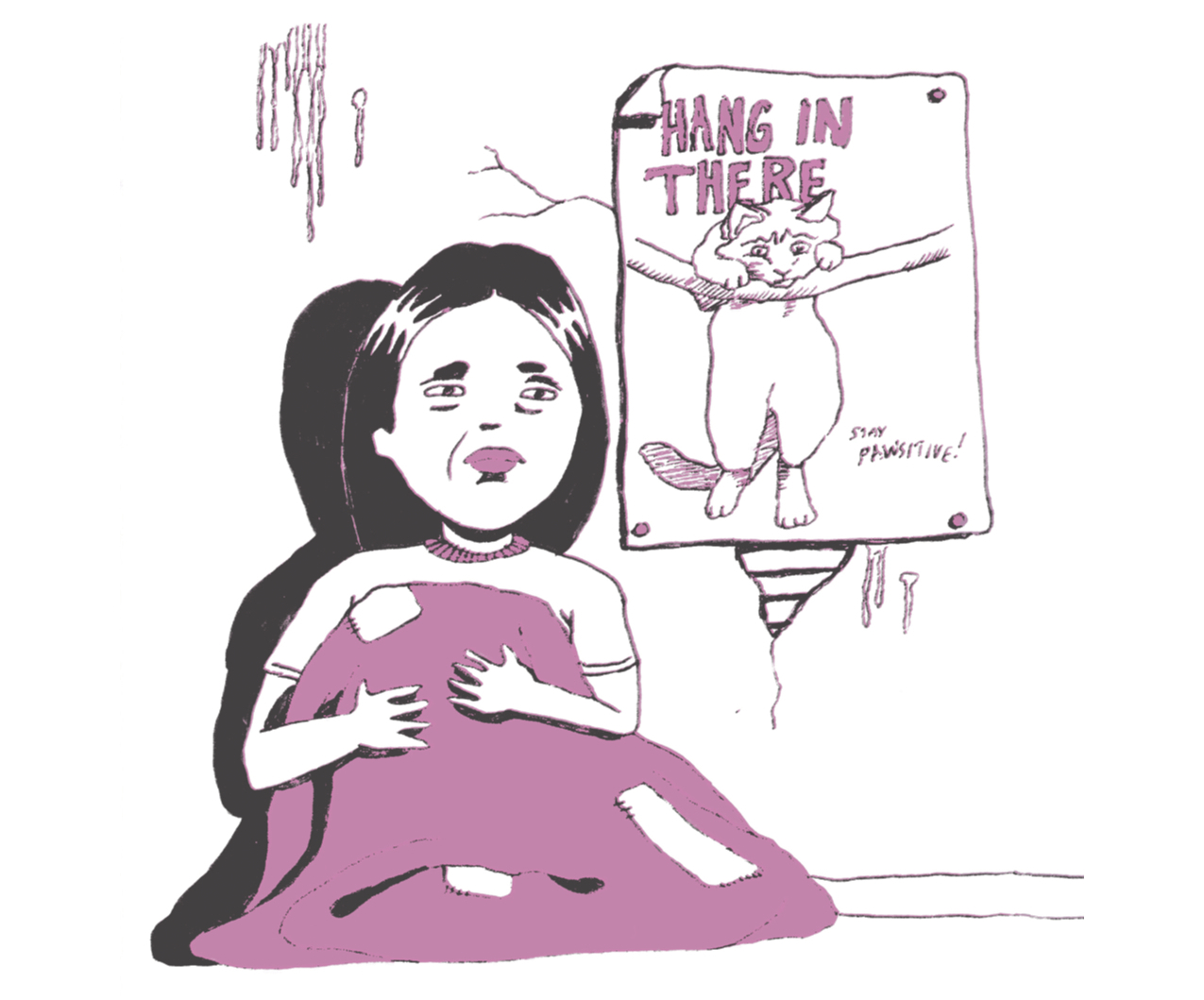

There’s an orange kitten grasping a branch, superimposed onto a sky-blue background. Hang in there, the poster tells me. Underneath someone scribbled “stay pawsitive.”

I chuckle every time I see it. If Cass were here, she would have already ripped it down.

The rest of the walls are littered with posters of bands I’ve never heard of, stickers stuck on top of stickers, and a haphazardly painted banner proclaiming “Go, Manatees, Go!”

Most of the college was ransacked long ago. The only things I found were a few cans of tomato soup that fell behind the cafeteria’s fridge and a moldy blanket that I repurposed into a bed.

But the station had been relatively untouched, tucked in a corner far from the rest of campus on the edge of town. Hundreds of CDs still lining the shelves, empty coffee cups scattered everywhere. I propped all the chairs against the door and covered the window with cardboard. Home sweet home.

The broadcast light is on. There’s still power, but no one knows for how long.

I press play. The small room fills with the sounds of Shaggy’s “It Wasn’t Me.” For the next four minutes, Shaggy tries to convince his partner that despite being caught in the act of fornicating with the neighbour on the counter, sofa, and shower, it was not, in fact, him.

When the song ends, I skip back to the beginning. Maybe today’s the day Cass will hear it.

Cass and I wore the same Sailor Moon shirt on the first day of kindergarten. That’s how we became best friends. In third grade, we put on puppet shows that only Cass’s dad would (grudgingly) watch. In sixth grade, she whisked me out of gym class when everyone saw me get my first period in the middle of dodgeball. In ninth grade, I bought three cartons of extra-large eggs and 12 rolls of toilet paper after He-Who-Must-Be-Named-DoucheDick spread a rumour that it wasn’t just a first kiss that Cass gave him.

In between that, we planned our escape. We would move to Paris together, open a bakery. Or maybe New York and revive our puppet show. Or literally anywhere that wasn’t here. We were going to blow this popsicle stand, Cass would say. I always told her melt made more sense.

Shaggy wraps up his plea, and I skip the track back to the beginning.

When Cass’s dad passed away, he left her his old radio cassette player, a box of mixtapes, and a note that said, “To get you through the hard times. Love, Papa.”

After his funeral, Cass and I laid on her bedroom floor. I put in one of the tapes and pressed play. We were silent for a minute as Shaggy’s smooth beats reached our ears.

Cass burst out laughing. “He’s dead, and he’s still a troll.” Cass sat up and wiped the tears from her face. “I can’t wait to get the hell out of this place.”

Yale had given her a full scholarship. In the fall, she would move 4,000 kilometers away. I only got a pity acceptance from the local college. Go, Manatees, Go.

I nodded, rearranged my lips into what I hoped was a smile. When the song ended, Cass put her head on my lap. “Play it again,” she said.

I was planning on wearing a red dress and black sneakers to graduation. Cass would have been valedictorian. We would have spent the summer at the beach listening to Shaggy, and then Cass would have left.

Instead I’m sitting on a carpet coloured by years of stains — dirt, puke, blood, and more I don’t want to think about.

But it’s just a matter of time before Cass hears the song.

After she finds me, we can figure out what to do next. They told people to head east — more people there, more resources. It’s supposed to be safer. Cass and I would go that way together. Most people seem to have already left. Headed east long ago. That was the smart thing to do.

Shaggy finishes making a case for his innocence. I skip back to the beginning and play the song again.

x

Wendy WL Chan is a Vancouver-based storyteller. Her writing has appeared in print in Shoreline and on stage at Brave New Play Rites Festival. She holds a BFA in Creative Writing from UBC and tweets occasionally at @wndwlc.