The final screening of DOXA 2017 was For Dear Life (2017) at The Cinematheque. If the audience was festival weary, they didn’t show it.

For Dear Life was preceded by the short For My Mother (2017) by Manny Mahal. The 18-minute film was one continuous take walking from a house around 65th Avenue and Fraser Street, to the parking lot of the Superstore along South-East Marine Drive. The camera movements mimicked footsteps, even looking both ways before crossing intersections. This, as the director recalled his mother. He talked about her experiences as an Indian woman in Vancouver, of her love for the Canucks, about her illness, and her transformative kidney transplant.

Aesthetically, it was nauseating. The camera motions were jerky, and slightly out-of-focus. While the anecdotes were delicate and loving, some of them showed so much unresolved angst that it was distracting. This didn’t detract from the overall impact of the short, however, which culminated in a devastating conclusion. The camera blacked out once reaching the Superstore parking lot, and we learned that the director’s mother was hit by a car and killed.

The audience was moved, many people weeping openly. Then almost too suddenly, For Dear Life began.

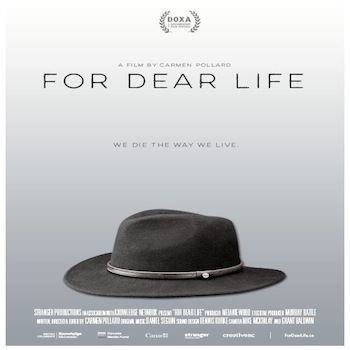

The feature documentary by Carmen Pollard depicts the final years of her cousin’s life following a terminal cancer diagnosis. Her cousin, James Pollard, had been involved in local theatre, and the two of them collaborated on For Dear Life as a creative project to work through their grief.

Though the audience was still raw from For My Mother, it was hard not to laugh during the first few minutes of For Dear Life. It began in a wood shop where James and a relative were building a coffin. James’ dimensions were measured and he was so lighthearted and jovial about the process, that the audience found some much needed catharsis.

From there, the film jumped back two years earlier. James had a full head of hair, looking anything but sick as he drove up Main Street and discussed the reasons for making this documentary. James remarked to the camera, “There’s no culturally acceptable way to crack a joke about someone who is about to die.” It’s obvious, however, that’s exactly what James intended to do. Right from the beginning, the documentary provides an honest look at the taboos around death, and how to cut through these restrictions find humour.

FOR DEAR LIFE trailer from carmen pollard on Vimeo.

James recounted first finding out about his cancer, and having it immediately change his outlook on life: “When you realize you’re dying, nothing you’re worrying about today matters, but the relationships matter.” The viewers were introduced to James’ friends and family over the course of the documentary. Every individual was at a different stage of grief and acceptance, but they are all working to strengthen their relationships with James before the end of his life. The most dynamic relationship was between James and his daughter Emma. What was no doubt a very intense relationship to film, documented one of the harder realities of having loved ones die slowly — getting overwhelmed witnessing death, and having your love for that person mingle with feelings of anger, resentment and frustration.

During a scene from James’ birthday, a cake is brought out. As family and friends sung “Happy Birthday” on screen, I heard people in the row behind me join in. In that moment I realized — of course — some of James’ friends and family were in the audience at The Cinematheque. The people behind me didn’t just know James, they had been at that birthday party. For Dear Life depicts James experiencing his own death, for the first and only time. But for James’ friends in the audience, they chose to watch James die for a second time, to be close to his memory again.

For Dear Life showed James as a fighter, attempting new cancer treatments whenever he could. When his doctor decided his cancer wasn’t worth treating anymore, James’ deterioration was rapid, and it was all captured on camera. His belly and feet became bloated, but his face and arms grew sunken. His hair started to grow back patchy on his head. His voice, once full and theatrical, became weak and weazy. James’ body became a shadow of what it once was, although his mind was still sharp. When James finally died, he was laid to rest in a custom-built coffin with clay. (James had designed it to slow his decomposition in case future scientists wanted to study his cancer.)

For Dear Life is a dark, beautiful and funny portrayal of death, with too many nuances to describe in a single review. Carmen Pollard edited the documentary masterfully, allowing for metaphor and reality to weave together. For Dear Life doesn’t just highlight Western society’s discomfort with death and dying, it challenges it with a true story that inspires living life to the fullest.