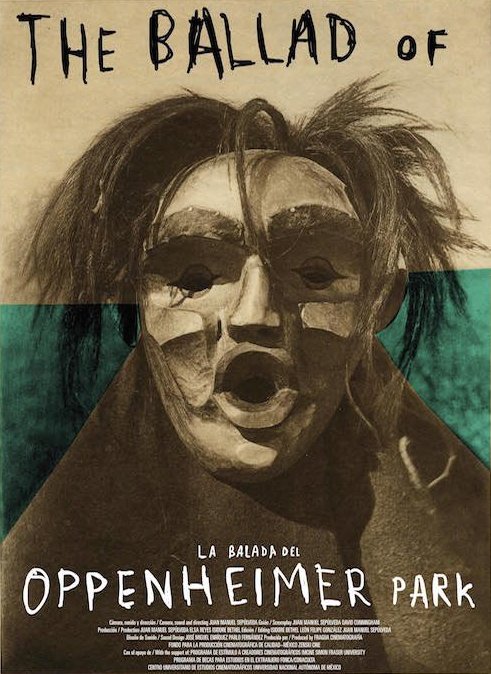

Sung of a park and its denizens — The Ballad of Oppenheimer Park can be heard in two key scales at once. The first scale tells the story of derelicts, not unlike Steinbeck’s cast in Cannery Row. Far from the Palace Flophouse, Ballad’s park-goers are indigenous residents of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Bear, Harley and their crew of friends, hang out and sometimes sleep in Oppenheimer Park. Similar to Mack and his boys in Cannery Row, they remain resilient to hardship through moments of generosity and friendship.

Heard in another key, Ballad is an ethical conversation about the film and its filmmaker. Director and SFU Film School graduate Juan Manuel Sepúlveda is considered a settler in Canada, meaning he is not an indigenous person. As a settler, his depiction of indigenous people in Oppenheimer Park — particularly those who face chronic mental health and substance abuse issues — is controversial. As a Western-themed documentary, Sepúlveda’s settler status adds the first layer of colonialism to the film; one that operates outside the screen, adding threat to the Oppenheimer Park “frontier.”

As Sepúlveda observes a variety of amiable and antagonistic moments between members of the Oppenheimer Park community, he experiments with the documentary genre. Using props, character placement and landscape, Sepúlveda fashions his film as a Western. Ballad’s opening scene shows a stagecoach burning in the middle of Oppenheimer Park. Flames peel back its canvas covering as the stagecoach sits ominous. This is the first of many props the audience may assume are inserted in the film by its filmmaker. These insertions become creative infusions in the unfolding relationships between the people of Oppenheimer Park: they are filmed wearing cowboy hats, playing cards and carrying a coffin solemnly into the park. Props place the film’s characters in a stylized setting.

Challenging the Western paradigm of “cowboys and Indians,” Ballad’s indigenous park-goers play both roles. Riding through the park on a stagecoach — presumably the same stagecoach that is burned in the opening shot — some chant, drum and dance. They are the park’s cowboys. Cowboys who fight for their honor and the Oppenheimer Park frontier, but remain simultaneously as indigenous people living within Canadian colonialism.

Two lifesize cutouts of indigenous people dressed in traditional clothing appear midway through the film. One is a chief in headdress, one a warrior holding a gun. The cutouts are addressed briefly by an indigenous man named Bear, but are generally ignored by people in the park, as if invisible. In one scene Bear and a woman sit on two separate benches with the warrior cutout between them. More than a reminder of the past, this cutout is a symbol of how identity is assigned and assumed. The presence of this familiar image of an “Indian warrior” challenges the audience to accept their indigenous cowboys also as “Indians.”

The film’s placement of characters and cinematic style builds on this theme of dualism. A number of shots show characters with visible faces and others with shadowed faces or heads turned away from the camera. This is, in part, due to the documentary’s single camera limitation, but this also functions to mystify individuals. The contrast of visible and unseen faces suggests that there are agents of good and evil at work. It also symbolizes the presence of “dark forces” inching mysteriously into the park frontier.

Long shots of the park at sunrise and sunset establish Oppenheimer as a desolate and flat landscape: another homage to the Western genre Sepúlveda consistently draws from. Where he deviates from this genre, is in the park’s unusual designation as “frontier.” Like a traditional Western frontier, it is a place of freedom, a place where mainstream colonial law and order is rejected, but, as the first words heard in the film assert: “You’re standing on stolen native land.” Once an indigenous cemetery, Oppenheimer Park now belongs to the Government of Canada. Defending Oppenheimer park as a “frontier” means allowing Ballad’s indigenous cowboys to redefine the standard Western notion of a “frontier” as something more nuanced.

In the film’s final scene, the camera takes us away from the park for the first time. It follows a person walking through some bush. The metallic sizzle of hot train tracks is audible. As the man exits the frame (possibly to catch a train), out-of-focus trees are all that remain in view. It is a blurry image. As Sepúlveda’s controversial role in the making of Ballad enhances the film’s trope of colonial threat — threat to honor, threat to freedom and threat to this newly imagined “frontier” — the audience is left with a ballad sung in two key tones, complex, but clear.