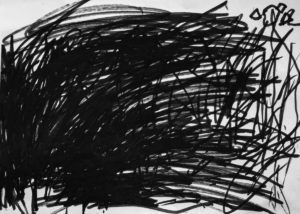

“Only a few metres were separating us from the first explosion. On one long summer night, they inched closer and closer. Underneath the continuous shelling, from the warplanes and artillery, I started sketching to express the stories of faces from death.”

Majdal Nateel, The Last Sketches 2014 Diary, 17 drawings, pen on paper, 34×24 cm

There is no better way to open this review than with Gaza-based artist Majdal Nateel’s words. Nateel is one of six Palestinian artists whose work was showcased at the exhibition On Borrowed time in Gaza: Art in Confinement at Vancouver’s Monica Reyes Gallery on November 2021. Other artists included Maisara Baroud, Maha Daya, Mohammed Alhaj, Rufida Sehwail, and Ganem Alden.

In 2014, Nateel was volunteering at a hospital in Gaza during the 51-day bombardment and airstrikes by the Israeili military. There, she witnessed deaths and trauma every day. The artist —who was seven months pregnant at that time — would go home and sketch every night. Her work is haunting and encapsulates the exhibition well by depicting what coming face-to-face with mortality every day looks like.

When I first started writing this piece I had a writer’s block, but unlike an average case of writer’s block, I wasn’t sure if I would get past this one. What could I say about the oppression and suffering of Palestintians that hasn’t already been said? What could I say about the ethnic cleansing at the hands of Israeli military and the government that hasn’t been documented? I’m not here to do that.

I have also tried not to dwell over my relative privilege, the prerogative of other attendees at the gallery, and the irony that we live in west coast Canada — in one of the most liberal cities, with the ability to move freely and express ourselves openly.

As I stood in the centre of the gallery, nothing jumped out right away. The drawings were relatively small scale — lines on flat sheets — something you could easily miss if you weren’t paying attention, especially in a time when our brains are constantly overstimulated and our attention spans are probably at their worst.

Upon closer inspection, I noticed how the artists had used different techniques: some worked with charcoal, some with pen or pencil, and some with watercolor. Yet, one thing united them – making art in confinement. While I was struck by the stories of grief and loss, of tragedy, of invasion and violence of bodies and homes, what most stood out was the perseverance, the resilience, and the immense solidarity.

“As I stayed at home I dedicated my time to Isolation Diary. In this work, I was free to move in a world I created, not affected by the restrictions of the blocade or by COVID. The diary intended to break time and space constraints. It breaks the intensity of dire times.”

Maisara Baroud, Isolation diary, Four series, ink and pen on paper, various sizes.

Another artist whose work really struck a chord was Maisara Baroud. Baroud’s drawings created a visceral experience of claustrophobia and captivity. Images of disjointed bodies falling in the sea, paper plane drones hitting the city’s infrastructure, and scenes of incarceration all felt like poignant parallels between the artist’s reality and the global pandemic, and how Palestinians have been denied agency and been facing one lockdown after another long before COVID-19.

In her work, Obsession with Memory, Maha Daya highlights the erasure and theft of Palestinian culture — appropriation as a result of ongoing colonization — and does this through painting motifs and patterns on pieces of fabrics.

Prior to this exhibition, I have never felt the absence of artists at shows before, not as much as I did here. I’m talking about feeling this literal physical absence, and imagining an alternate reality where borders didn’t matter and they’d be present.

The resistance of the Gaza-based artists was loud and clear which only felt like a stark juxtaposition to their lack of physical presence.

I have been to a handful of art shows during the pandemic. While the artists may not be physically present, you can tell that they have complete autonomy, they curate the show based on how they want to be percieved by the outside world, similar to how a lot of us carefully compose our grid on Instagram.

This made me wonder how much of the same liberty do Palestinians have, in their creative and personal lives.The artists and I were separated by geography, time, and space. Did that make the experience more palatable? Not having to witness the faces behind the artwork, did it make it less real, or just real enough?

I felt like a voyeur at times, peeking inside someone’s home while they weren’t there. Here I was, leisurely skimming and scanning the art along with the other visitors, carrying our privilege with us as casually as our tote bags, perusing the blurbs and examining the drawings —our only means of connections with the artists.

We were free to leave the gallery at any point and move on to the next cultural event, unlike the artists living on borrowed time. As I was about to head out the door, I noticed there was an entire wall in the gallery filled with children’s art. The drawings were created as part of an art therapy program for children with cancer in a hospital in Gaza. Most sketches had depictions of drones, airstrikes, and army tanks in common. A few had images of houses with Palestinian flags and drones pointing towards the houses.

The children were succinct with their art.

They told it as they saw it, no metaphors, no analogies, just a raw glimpse into the everyday lives of Palestinians.

Perhaps that’s why it was the most unsettling part of the event. No layers or symbolism packaging the truth, only the cold reality staring right at you.

This review would be incomplete without mentioning Rehab Nazzal, the curator of the exhibition who is a Palestinian-Canadian artist as well. The journey of how the artwork arrived in Vancouver is nothing short of a scene from a Martin Scorsese film. In 2020, Rehab was in Gaza working in the art therapy program which I mentioned earlier.

During that trip, she met the six artists, who would later be featured at the gallery. They shared their hardships of creating art under the brutal Israeli blockade in Gaza, which has marred the lives of over five million Palestinians for more than half a century. The artists also relayed the struggles and barriers they face in bringing art supplies into the city and taking the artwork outside Gaza.

That’s when Rebab got the idea of showcasing their work in Vancouver. Sneaking the art pieces out of Gaza was an ordeal but Rehab was adament.

She packed the artwork in her bag, taking off the frames and making the artwork as flat and invisible as possible. The drawings — in essence, the artists’ stories — were hidden in a bag as they were smuggled from the Gaza border past army checkpoints, loaded on a flight to Toronto, and from there flown to Vancouver.

Making art in Gaza is not only a matter of self-expression but a literal act of survival, an act of resistance, and an act of protest in the face of harsh conditions in the world’s largest open-air prison.

The artists in Palestine are deprived of their right to free movement, their right to dignity, and their right to connect with the art community and public; but all of this has not diminished their spirit and not stopped them from making art.

Therefore, the lines between the art and the artist really blurred. The six Palestinian artists became their art, and it filled in the gaps where these artists could not be physically present. However still, leaving a lasting impression, and a lingering presence in my mind long after I left the gallery.