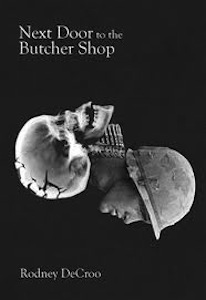

Rodney DeCroo, a Vancouver singer-songwriter of grim blues / rock, released a book of poetry in 2017 titled Next Door to the Butcher Shop. His writing does not depart stylistically far from his music; his moody verses are sometimes narrative, sometimes expository, often brimming with nostalgic anger. In fact, reading this book while listening to his music is not altogether disorienting, granted you have the volume down low enough to obscure the lyrics.

If you are familiar with DeCroo’s work, you will likely know his childhood of abuse and the resultant PTSD and drug use that plagued him in adulthood. In both music and writing, he tends toward the autobiographical. Being aware of his history lends poignancy to his poems. “Black Columns” is an elegy of sorts addressing his “Indigent father,” a ghost who “haunts the bus stations of Appalachia.” The poem alludes to the experiences of his father, uncle, and grandfather in Vietnam and the Second World War. DeCroo acknowledges that much of his work is built on suffering (“They pay me because my head is broken”), inferring that his career is a culmination of “three generations” of violence, a career they collectively “earned […] like a wage.” As a result, his father appears a victim of familial and historical violence. This is an extraordinarily forgiving view of someone whose abusive habits are well documented in Rodney’s songs.

Sometimes DeCroo slips into gory imagery but the real horror remains his actual experience. In “The Chair,” he writes “A liver, a kidney / a lung, a deformed and oversized heart / to lug around like a pot roast / among his rags and bottles.” It reads like a laundry list of maudlin metaphors that is, at times, self-indulgent: “I wanted to fuck my way back to the nothingness I came from / I wanted to burn God’s face off with a flamethrower.” However, he is usually more incisive and sparing, and grants grace in the aftermath of brutality. It is only when he abandons the vitriol can one see the ghosts lingering behind it.