Part musical, part documentary, Tomorrow is Always Too Long is perhaps most effectively described as a multimedia collage. Its defining visual elements include blasts of public access TV-meets-YouTube clips intertwined with silhouette animation reminiscent of Lotte Reiniger’s pioneering work.

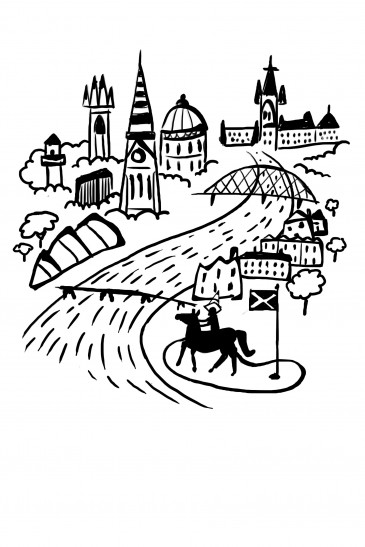

The film is also the ultimate exercise in collaboration as filmmaker Phil Collins — British video artist, not the guy from Genesis — is joined by an auspicious crew of writers, animators, indie musicians, an orchestra, and everyday Glaswegians who come together to create an endearing, bizarre homage to Glasgow, Scotland.

Are you with me now?

At its core, Tomorrow is Always Too Long is a musical documentary, the most understated, glorious film genre in which ordinary folks sing their story, superseding the more traditional talking head interview. Collins features a wide cross-section of brave ordinary Glaswegians in his film who surrender to song, if only for three minutes, breaking free from the drudgery of daily life.

The chosen subjects span the generations and social enclaves of Glasgow, from punk-rock parents in a birthing class to preppy teens singing in a classroom as a teacher leads them through an unmistakably pre-pubescent dance routine. There’s also a young man singing in his jail cell, as well as an elderly couple who wail as they weave themselves around a ballroom dance floor. Each musical sequence is set to Cate Le Bon’s 2013 psych-pop album, Mug Museum. What makes these “covers” extra special is that Le Bon’s songs have been rearranged and performed by the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, making for larger-than-life musical breakdowns.

Musical sequences aside, the rest of the soundtrack is scored by Mogwai’s Barry Burns and Glasgow locals Golden Teacher. The often eerie, electronic soundscape these musicians create accompany shadowy animated sequences from Matthew Robins. His silhouette animation depicts pleasure-seeking creatures, both human and animal, in voyeuristic scenes humping in the forest, snorting lines in a bathroom stall, and drinking alone at a bar. Their eyes are cut-out holes, allowing the background to shine through. There’s something about this transparency, combined with the non-stop debauchery that make these creatures vulnerable, disturbed, and the most human of all.

Between the musical numbers, and interlaced with some of the raunchy animated sequences, is an imaginary TV channel. It features an assortment of sardonic vignettes with an aesthetic reminiscent of early ‘90s public access television. There are fake commercials for made-up products, such as “Search Me,” a device that guarantees anyone wearing it will succeed in getting a groping from airport security; a game show in which contestants nonchalantly answer questions about pop culture and terrorism; and most poignant of all, a disgruntled mystic, whose 1-800 infomercial is centered smack dab in the middle of the film. In the longest single-take of the piece, she laments technology for an increasingly alienated society and longs for a time when people were genuinely connected.

But in Collins’ film, it is clear that “online culture” is not the only thing to blame for isolation: the cityscape and institutions also play a considerable, disruptive role.

Simply describing Collins’ erratic film is hard enough, so trying to make sense of it is another feat altogether. But what I liked most is that despite its frenetic pacing, the structure is cyclical, self-reflective, and almost soothing. While themes of alienation run wild — whether it’s due to technology, institutions, or the city itself — there’s a warm air of nostalgia that breezes through each scene. Collins’ wacky brand of storytelling shows that sometimes it’s easier, and more satisfying, to re-create the past than it is to imagine a future. For if tomorrow is always too long, then yesterday wasn’t long enough.