“Respire turned their eye outward on Black Line — writing about the ills of the world, rather than the sicknesses of the self.”

“Black Line is intense, but rarely escapes the band’s control. Instruments, like brush thirsty for embers, are set ablaze and removed to make room for new growth.”

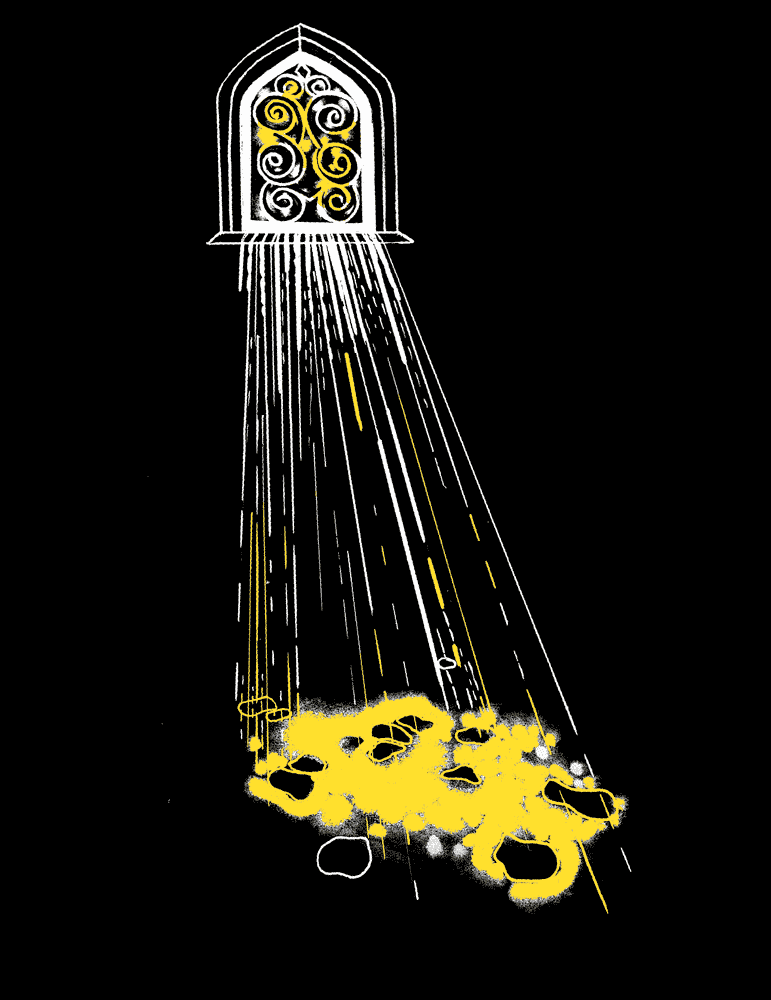

A burning structure serves as the frame in the image I am looking at. Though it is ambiguous if this burning frame was erected for the purposes of the photo, or if it is some found ruin off a highway, it recalls landscapes that people who have travelled through the country know well. The six people in the photo, standing beneath the burning arch, are the current core members of Respire, the self-proclaimed “Post-everything” Toronto-based collective which has set out to defy the boundaries of bandhood, and the claustrophobic confines of what most of us understand as “heavy music.” The photo is part of the press package that was sent out to me prior to my conversation with Rohan Lilauwala, vocalist, guitarist, and founding member of Respire, who acted as the band’s mouthpiece for this conversation.

After a brief introduction discussing their humble beginnings, Lilauwala summarizes the project’s conception; “The much briefer pitch is: We were all playing music, sort of together, sort of in different groups, and we decided to come together to create something more ambitious than we were doing at the time in any of our projects. Not just musically ambitious, but conceptually ambitious.” He explains that prior to Respire, many of the members knew each other through playing in other bands and booking shows together, or by simply existing in the Toronto punk scene. This combined desire to create something beyond the reach of their past projects would propel the band to write 2016’s Gravity & Grace, 2018’s Dénoument, and their latest offering, Black Line, which was released in December 2020 by Church Road Records.

This ambition manifested itself early on in a desire to incorporate instruments not usually found at the forefront of post-hardcore albums. The original Respire makeup featured Emmett O’Reilly on trumpet, which melded well with the band’s sombre dirges. As the years went by, Emmett had to retire from being as active within the band, and trumpet came to be replaced with violin in the hands of Eslin McKay. For Respire though, no one is ever really gone. Their approach to managing the band as a true collective, rather than the usual and romanticized “give all, give everything” attitude — ubiquitous in genres like punk and hardcore — pays off in a number of ways. For one, it allows them to remain flexible in terms of membership. Though Emmett has not been a regular member of the band since Gravity & Grace, he has made an appearance on every Respire album to date — and is always welcome to participate in the band’s live shows. Respire refers to this as their “open door policy for the extended family,” a model that has gained some traction in recent years, but remains largely underutilized by their contemporaries.

This familial approach serves the project’s ambitious goals, which could be easily stifled by the band’s own technical limitations. “The reason we’re able to draw out all of these influences and do the things we do is because of our collective approach to songwriting […] We don’t want to be limited by the skills and talents of the people who have the time to be in the core membership of the band.” Lilauwala continues, “We’re always considering how to incorporate the talents, skills, and ideas of other people in our musical process.” The extended family goes on to include even reoccurring audio engineers, which affords the band the flexibility to record their massive albums, with consideration for their budget, and every members’ availability. Though Respire can be slow-moving, their pace makes sense to me. It takes a particular kind of patience and attentiveness to create the kind of layered music they set out to write — especially for a band that has adhered to DIY ethics for the majority of its existence. Corralling band members for practices, studio sessions, videos, photoshoots, gets harder as their numbers grow or fluctuate, and harder still as the reality of being a musician often means that resources — like time and money — are also devoted to personal responsibilities. Lilauwala doesn’t kid himself, and even jokes that “[Respire is] a negative bill payer in that it has bills.” But even in the face of this reality, the band’s model allows them to create at a steady pace and thrive.

Though the band’s ethos is evident throughout their discography, it is definitely in it’s most polished and refined form in Black Line. Having learned lessons from their past recording experiences, Respire made intentional decisions in effort to create music that surpassed their previous efforts. Choices such as; recording drums in a separate DIY studio as opposed to live-off the floor with the other instruments, scoring out all of the guitar and bass tracks to avoid unintentional dissonance (also to give the other instrumentalists an idea of what to write around), and alloting a month for simply listening, demoing the bones of the songs. Once these were set on tape, the band booked some time at Array Music in Toronto — a studio space geared towards avant-garde music-making. “There were just so many toys,” Lilauwala chirps with vivid excitement, “there was a grand piano, a gong, a vibraphone, all these instruments that we’d never have access to otherwise.” This short stint at Array provided the band with the ability to experiment with otherwise unusual instruments, even choosing to replace some of rock’s classic tools altogether at points. Though Respire definitely took cues from Canadian post-rock legends Godspeed You! Black Emperor, among others, the resulting music is far more aggressive — scaffolded by the band’s love of emo and hardcore. Unlike many of their genre contemporaries, the added instrumentation and experiments sound as they intended —considered and necessary.

The theme of fire is central to Black Line, the title itself a reference to a fire management term used to describe a treeline that is control-burned to contain the spread of wildfire. “The theme of fire as something that can cleanse and purify, but also destroy, really appealed to all of us,” explains Lilauwala, “We need to destroy some of the ugliness in our society and the things that are eating away at us, whether it’s bigotry, fascism, climate denial […] These are the things we need to destroy as a society to heal, move forward and survive.” Simultaneously a warning and a call to arms, Black Line observes the world in a dire place, and the plight of the music is drastic but arguably necessary. Though Respire was writing the album prior to the events of 2020, Lilauwala sees the album’s relevance in today’s political climate and is not shocked that the subjects they began to write about three years ago have come to a head recently. “The events of 2020 didn’t come out of left-field by any means. They are a culmination of a number of trends that have been going on for many years,” he observes. Moreover, he notes how being Canadian has always served as an excuse for people to disengage from politics. Even now, the imaginary line created by the southern border with the USA is enough for Canadians to believe that bigotry and far-right ideology have not set root in Canada. “We have RCMP standing around while settler fishermen set fire to Mi’kmaq fisheries. We have pipelines being pushed through unceded Indigenous territories by oil companies with the aid of the federal government. Black, Indigenous, and brown people being incarcerated at disproportionate rates […] We have the same undercurrents as the US.” Maybe with a degree of responsibility then, Respire turned their eye outward on Black Line — writing about the ills of the world, rather than the sicknesses of the self. Lilauwala concludes, “the best time to set the stage for healing in 2020 was before 2020, but the best time to do it now is now. Our message still stands. It’s still relevant.”

As I observe the photo of the six members surrounded by fire, I see the connection of the element to the album as more than a simple thematic. I see artists wielding fire, harnessing it, and using it as a tool for creation rather than a weapon of destruction. The band’s attention to detail, their collective intent, and their meticulous approach to songcraft draw comparisons to a fire management team, containing the power of wildfire. Black Line is intense, but rarely escapes the band’s control. Instruments, like brush thirsty for embers, are set ablaze and removed to make room for new growth. Lessons were learned from past skirmishes. Members support each other, bring their own skills and resilience, working together to harness the versatility of their music which — much like fire — is as hostile, unrelenting, and destructive as it is beautiful and warm, brimming with magical life. As for the burning frame in the photo, I envision the fire eventually turned it to ash, and what is left is an image of a family against a limitless blue sky, unbound.