Editor’s Note: The following essay is a reprint of an edited Facebook post from August 11.

This letter is a response to CBC Radio One’s August 11, 2017 coverage of the Vancouver Mural Festival on the program The Early Edition.

❇︎

This morning CBC’s The Early Edition did a piece on the Vancouver Mural Festival (VMF), scored by the theme music from web series turned television series Broad City. Broad City is based on Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson’s (Jewish American comedians and writers) real life friendship, and their attempt to “make it” in New York. The show opens with a colourful animation done by Mike Perry and the theme song is a track called “Latino & Proud” by Chilean hip-hop and electronic music producer DJ Raff.

Yet the intent behind this song choice is misleading. Vancouver Mural Festival, at the core of its structure, does not represent a culturally diverse or marginal perspective as you might expect from a mural festival. Instead it is the initiative of a group of predominantly white men who have built alliances, not with the everyday people of Vancouver, but with real estate developers, Business Improvement Associations (BIAs) and the City government.

A group of Mount Pleasant residents have recently done some questioning and investigation into the funding structure, power alliances, and implications of the City of Vancouver’s support of Vancouver Mural Festival. This story weaves the personal lives of Mount Pleasant residents, the sun-setting of a cherished local building known as The Belvedere, and the political and economic structures that are driving the VMF, among other aspects of the equation. We would like to state that this criticism is directed towards the VMF founders and leaders, not the artists who have been hired by the festival to fulfill its goals. The VMF is opaque about its payment policies for artists, but they pay the artist on average $2,000 per mural. These are adequate contracts for working artists in this city, who on average, do not earn more than $12,000 annually.

As we have discovered, the City of Vancouver circumvented its cultural policies by providing massive startup and operational funding for Vancouver Mural Festival. The City granted levels of support previously unheard of when compared to the funding received by long-standing cultural organizations in Vancouver. The VMF sidestepped public art processes, accountability on allocation, and adjudication procedures, receiving a unique grant agreement based on a quota, not content system that has increased its coverage this year to a minimum of 50 buildings. Moreover, the start-up funding provided by the City did not arrive from the City of Vancouver Cultural Services but rather through the Engineering budget. This was a quick way for the city to run with a branding scheme for neighbourhoods in a way that ultimately serves the interests of developers, realtors, and property owners — stakeholders Vision Vancouver is beholden to more than working class residents who live in these areas.

At a basic level, the Vancouver Mural Festival represents an unprecedented cultural authority working in parallel with corporate and land-owning interests in the selection and approval of public art. Given that the festival’s programming and selection process rests primarily on securing buildings that say “yes” to a mural, the landlords and developers behind these buildings end up with the power to pick and choose what mural designs go up. The Belvedere Court is perhaps the most painful example of this force.The Belvedere is a beloved heritage building found at Main and 10th and is home to dozens of artists over the last 30 years including Derya Akay, Rebecca Brewer, Julia Feyrer, Tamara Henderson, David Lehman, Ron Tran, Alison Yip and Jacob Gleeson among many others. The Belvedere is also where Jean Swanson recently staged her city council by-election campaign launch, and she drew attention to the fact that The Belvedere’s landlords are currently in the process of renovicting residents en masse. With the vacant units in the building now at eight (or nearly one third of the total units) after a recent wave of evictions, bribes and fixed-term leases signed under duress, it is expected that the remaining tenants will be under intense pressure to succumb to no-fault evictions in the near future.

Ironically, given Vancouver Mural Festival’s message of improving neighbourhoods and communities, their flagship mural, titled “The Present is a Gift,” adorns The Belvedere and its painting was the catalyst that began the renoviction process in the building this past year. At one point, the VMF consulted with the Mount Pleasant Heritage Group (MPHG) for the mural – one of the few instances of such community consultation by the VMF. The MPHG proposed the phrase “Our Place, Our Home” for the mural text. It was rejected by the VMF in favour of the current platitude and the building landlord blocked the muralists from using portraits of two Belvedere residents from being used in the final piece. VMF organizers accommodated the landlord’s choice over the long-time tenants in its “community outreach,” thereby creating a sense of embitterment for residents as they were forced to gaze at a phrase quite in contradiction to their lived circumstances.

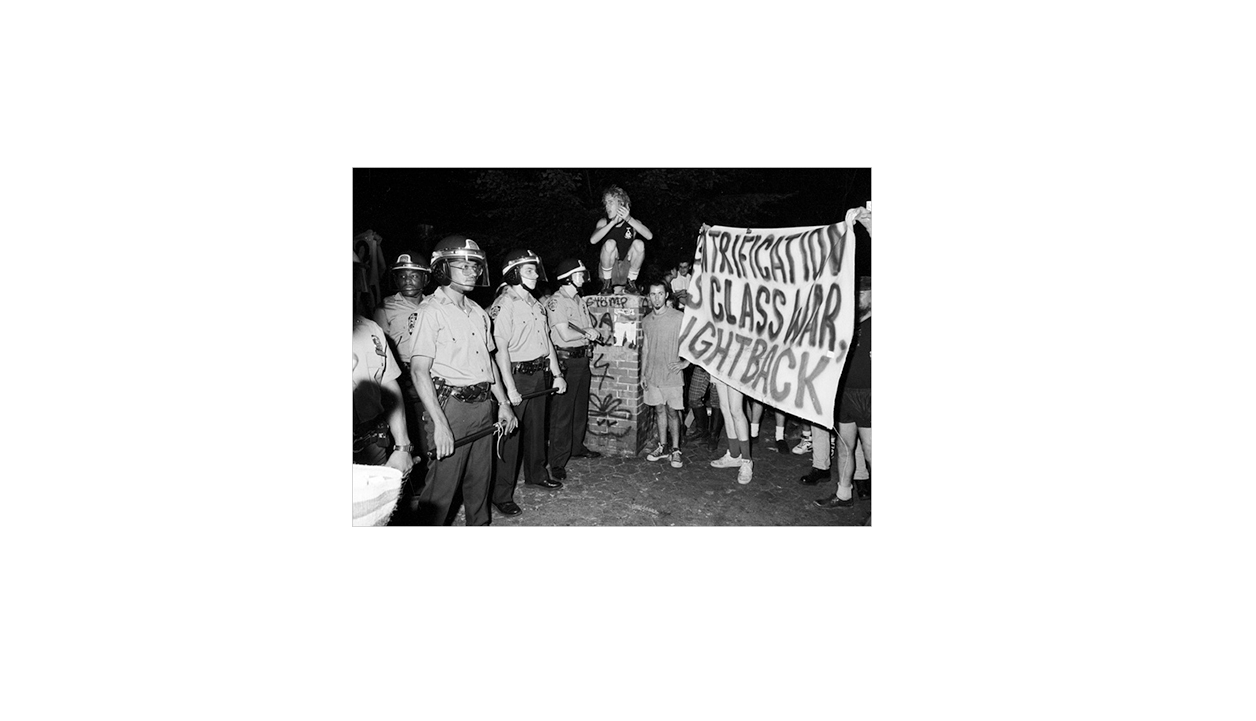

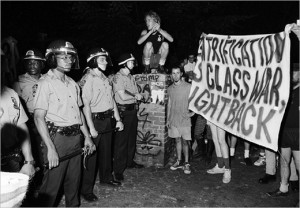

Speaking about the Belvedere mural, Festival Director David Vertesi is quoted in a Vancouver Sun article as saying, “it livens up a dead space… It is a really awesome reminder to appreciate what you have and to see the kind of people and diversity of people who call Mount Pleasant home. This piece in particular means a lot to me.” For the diverse residents in the neighbourhood living precariously under threat of eviction, such comments by Vertesi are utterly tone deaf and run roughshod over any other narrative that is not primarily fueled by development. VMF are acting like surveyors by priming a neighbourhood slated to be clear-cut in a truly unsustainable way. Ultimately the backroom maneuvers and financial backing of the VMF portray a strategic process of gentrification that’s being propelled by class interests amidst a housing crisis. The squatters and punks who stood off against cops at Tompkins Square Park in New York in 1988 summed it up best: ‘Gentrification is class war.’ And Vancouver Mural Festival is a blatant symptom of how class war is being waged in Vancouver in 2017.

With mass amounts of funding from the City – $550,000 in 2 years – $300,000+ from developers this year alone, $30,000 from Mount Pleasant BIA, and sponsorships from tech company like Hootsuite (who got several massive murals in the deal), all amidst the condo-fication of residential spaces and the rezoning of light industrial lands into tech campuses, the Vancouver Mural Festival spells out large-scale culture-washing for the Mount Pleasant neighbourhood. Queue Broad City theme: “4 and 3 and 2 and 1.”

What are the motives and what are the ends? Vancouver Mural Festival has been able to expand further into the Downtown Eastside (DTES) with vigorous support from Chip Wilson and his holding company Low Tide, who now own 5 buildings in and around Hastings and Hawks. If you look at the VMF map, many of the new murals will be in the DTES and Strathcona and we have the Strathcona BIA, Low Tide and VMF attempting to rebrand Strathcona as an “arts district.” Who really has licence to decide that a neighbourhood will be an art hub while it’s still literally in a state of being torn down and rebuilt? The placement of these murals should be at least suspect, in their alignment with top-down corporate strategies of urban renewal instead of a city-wide peer assessed arms-length arts funding process.

The quota-based process that the Vancouver Mural Festival and the City of Vancouver have mandated is aligned with the accelerated development in these regions that is displacing residents and single proprietor businesses. Meanwhile, leaders across several sectors have intently encouraged this rebranding scheme as a community amenity. Ultimately, there is a chorus effect at work, and everyone involved in leading these processes should be asked to reconsider how they are working, what the real-life effects of their work are, and to take some time to earnestly listen to the residents in the neighbourhoods being directly affected.