Time Flies

by Mark Fernandes

When 10 musicians take the stage each night at the Western Front this month, the results will be unpredictable. Time Flies is a rare opportunity for musicians to play a music festival without any preconceived notions of line-ups or compositions. It is an open concept, improvisational event where the musicians decide who they will play with each night. To invert the words of William S. Burroughs, everything is permitted and everything is possible: from a quiet duet between bass and piano, to live electronics interspersed with tenor sax or a caterwauling wall of noise created from a rewired Speak and Spell toy.

Time Flies, which runs from February 6-9, is brought to us by the Coastal Jazz and Blues Society. They invited eight musicians from places like Denmark and Montreal and even local known talents from Vancouver. This is a rare chance not only for audiences to watch great improvisation, but for musicians to acquaint themselves with others from different cultural backgrounds and milieux in an open dialogue without words, but sound.

The impetus to explore this musical dialogue of cultures surfaced in 1976 with one of Britain’s finest guitar impresarios, Derek Bailey, who inaugurated the first version of his Company. Through Company the intention was to create a fluid ensemble of improvisational musicians, coming from a variety of cultural traditions and musical backgrounds. It ended up becoming a wildly successful concert, attracting talents from Europe, North and South America, Africa, and Japan.

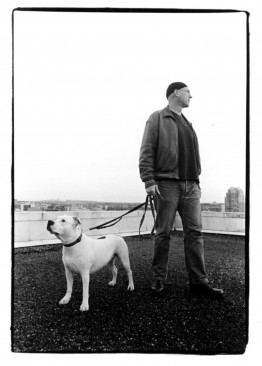

This year’s Time Flies has attracted quite a variety of musicians including German bassist Torsten Muller, who recently moved to Vancouver. He is a very flexible improviser who recently played two concerts here with Chicago reedsman Ken Vandermark and Vancouver clarinetist Francois Houle.

This year’s Time Flies has attracted quite a variety of musicians including German bassist Torsten Muller, who recently moved to Vancouver. He is a very flexible improviser who recently played two concerts here with Chicago reedsman Ken Vandermark and Vancouver clarinetist Francois Houle.

Improvisation can expose not only a musician’s technical abilities, but also taps into their listening abilities and emotional capacities. Muller explains why even in this atypical environment a musician has to be a master of self-control to work well in an improvisational situation.

“What usually happens is that if a player has strong empathy with other musicians then it will happen immediately because if you feel that there is something there it will work,” says Muller. “If it doesn’t work right off well there is no empathy, and no amount of preparation can change that.”

He is quite excited about this year’s line-up, mentioning his personal interest in working with pianist Thomas Lehn, who he used to work with in Europe, as well as Canadians with whom he is unfamiliar, like Montreal-born pianist Marilyn Lerner and Vancouver-based violinist Jesse Zubot.

Muller says he enjoys North American players because he hears a more indistinct and open-minded sound, as compared to the players he worked with in Europe. He describes the two very opposite contexts of art scenes here and in Europe.

“In Europe there always has been more money around for the working musicians to hone their styles,” says Muller. “A person like Alex Schlippenbach has a distinct personality that is ever-present and ready to define a context wherever he is. But here in North America there is a lack of money: musicians have to get day jobs in most instances which leads to a more indistinct sound that will be open to different kinds of music, because improvising is what you do and who you are.”

He acknowledges his own background and his own rebellion against formal European classicism, but he feels times have changed from the thundering anti-aesthetics of other German legends like Schlippenbach and Peter Brotzmann.

“I think there used to be tension more in the ’60s in Europe and through improvising the musicians had an attitude of ‘We are fighting for a liberated society.’ It’s not that way anymore,” he says. “You’re having a strong emergence of those who are coming from the classical scene, like Giorgio or others who use rock music as an influence. That’s why I moved here, for the diversity of musical backgrounds which I find fascinating, listening for the abstractions of sound and the fractions of minimalist ideas; people really forge out their own musical styles.”

Italian electronic music artist Giorgio Magnanensi disagrees with Muller about music moving beyond politics. He says that the current political shift to the right is fostering an environment of socially conscious musical personalities.

“It [Europe] changed in a way that led to more isolation of improvising musicians,” says Magnanensi. “Austria and Italy are fascist governments, politically speaking. There are not many places to perform, and a lack of money and support for younger, less accomplished musicians.”

Like Mulller, Giorgio Magnanensi is now a Vancouverite, and says that he feels renewed in this musical context. He shares a great disdain for Europe’s history as a colonizing force. “There is a lot of fresh, naïve energy here with no strong history of anything imported from Europe.”

Magnanensi highly regards improvisational music. He is an adventurous composer and improviser who uses everything from computers to CD players to electronic processors—even the outrageous, rewired children’s toys Speak and Spell and Speak and Math.

“Composing is out of time, while making live music is a chronological process, real time,” Magnanensi quotes from outsider composer Giacinto Scelsi in discussing how even in improvisation there is an implied formal structure. “Sclesi said ‘Music needs sound to exist, while sound has always existsed prior to music’. Music is the formalization of the external sound which is everywhere. Improvisation implies freedom, that is just anarchic juxtaposition of everything.

“I bring with me my culture because I am conditioned in some way by it.”

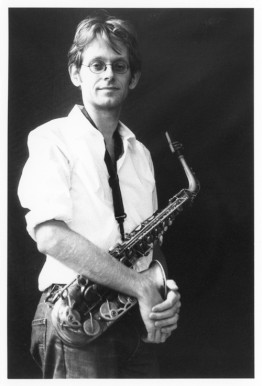

Also taking part is Denmark’s saxophonist/composer Jorrit Dijkstra, who promises to play the first ’70s electronic instrument, the lyricon, along with electronic music processing of his sax.

Also taking part is Denmark’s saxophonist/composer Jorrit Dijkstra, who promises to play the first ’70s electronic instrument, the lyricon, along with electronic music processing of his sax.

Dijkstra’s musical influences are far-ranging, including European improvisation, African and Balkan and even more formalist classical traditions. “I’ve always liked to observe differences in how Dutch, French, English, Norwegian or German improvisers have differ views on improvising,” says Dijkstra.

He believes that each cultural milieu and language will influence your musical personality. “I feel that in countries with harsher languages like Dutch or German, the phrasing and timing of musicians is also more edgy,” he says. “Let’s limit ourselves to Holland now, and you’ll see that a lot of Dutch improvisers and composers work with sound and textures, mostly short and lots of attack. Also in Holland I feel there is a lot of interest in clarity—short, compact forms and attention to details. This comes all straight from Dutch culture, an overpopulated flat place (no stretchy landscapes) and a language with lots of attacks and short harsh sounds and a place of irony and indirect humour.” Dijkstra, who was in Boston for the interview, says he cannot wait to go to work in Vancouver.

“I’m very happy that the festival lasts four nights, so we can get to know each other and learn each other’s musical corners.” •