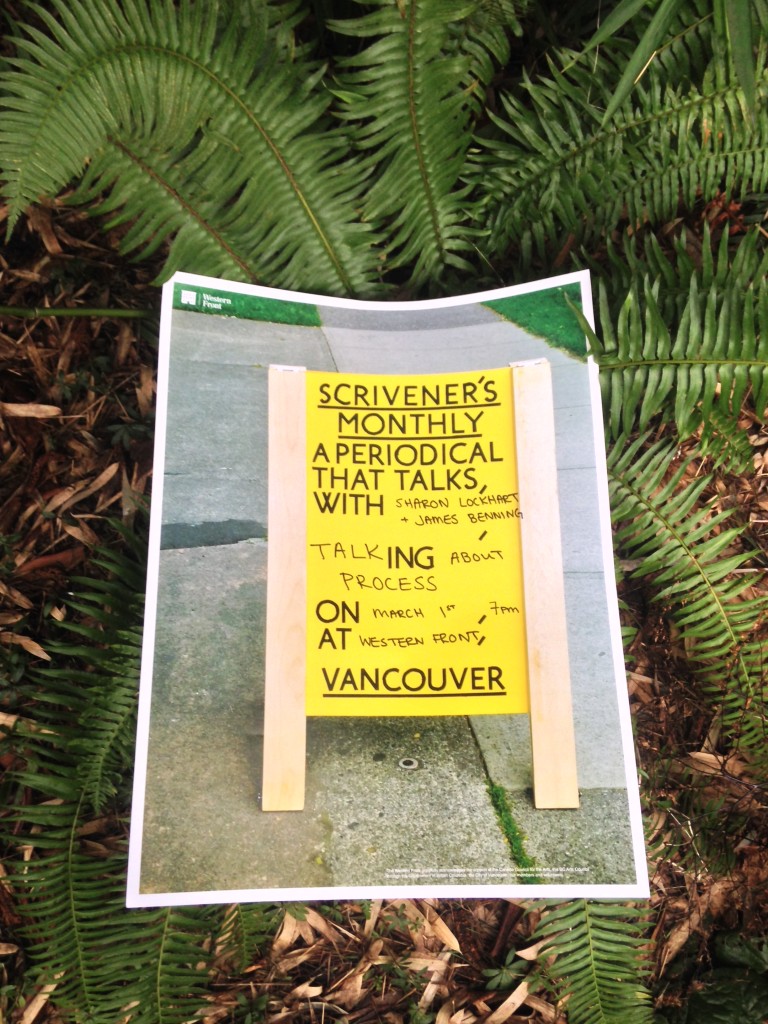

“Thanks everyone for coming to Scrivener’s Monthly, though if you know anything about us, you’ll know it’s not monthly, but anytime we feel like it,” began Pablo de Ocampo, Exhibitions Curator at the Western Front. And for anyone who has been to a previous Scrivener’s Monthly, you’ll also know that attendance varies. For this instalment, featuring filmmakers Sharon Lockhart and James Benning, the Grand Luxe Hall was full.

Though busy, the room went silent when Scrivener’s Monthly started. After a short land acknowledgement, de Ocampo invited Lockhart and Benning to introduce their films. Benning, whose L. Cohen (2018) screened first, opened with the line, “I was very influenced by a young poet who wore a suit.” He explained meeting Leonard Cohen, and perceiving him as someone who was always seeking a “spiritual window” through his music and poetry.

Lockhart kept the introduction of Rudzienko (2016) short, explaining that it was the second film she had made in Poland, and that it was “about resilience.”

Cohen is 48 minutes of a single shot of a farm field in Oregon. Ahead is what looks like a large stretch of green hay or alfalfa. To the left of the frame, perhaps 10 metres away, are a couple rusting barrels with some rubber tires leaning up against them, and a bright yellow plastic container next to it. To the right of the frame is some tractor equipment. A fence and telephone lines trail off to the right, with the faintest suggestion of a barn and a road in the distance. Directly ahead, many kilometres away, is a large mountain — Mount Jefferson — whose snowy peak is only barely visible through thin grey clouds. A bit of wind rustles the grasses. A microphone picks up the sounds of birds, flies, and what seems like the hum of airplanes overhead.

In his introduction, Benning had admitted, “You think nothing’s happening, and then something’s happening.” It isn’t a spoiler to say this film was shot during last year’s full eclipse, but I won’t describe what that looks like, only that it is surreal. And Leonard Cohen is there, sort of.

The audience had been warned that Rudzienko would begin shortly after L. Cohen and when the lights came on, people rushed to refill their wine glasses and fight for better seats.

Rudzienko opens with a black screen and the voice of a woman speaking Polish, words of a poem that we would later see translated into English in white letters. The first scene is a landscape with crossroad where two flat bike paths meet. There is a large tree in the centre of the frame, being whipped by strong wind. Cumulonimbus clouds, textured like scoops of hard ice cream, float quickly by. A couple cyclists pass, and some girls emerge from the tree. A cloud blocks the sun, the sky goes dark, and the scene changes.

Now there is white text dialogue on the black screen, a back-and-forth conversation between two young women, about God and loneliness and people leaving. The next scene is a pine forest with some sunlight passing through. Two women are lying on the forest floor, one woman horizontal to the camera, with the other woman’s head resting on her hip. The setting is calm. They speak to each other in Polish, and it becomes apparent that the dialogue from before is the translation of them speaking to each other.

And so Rudzienko continues like this, with young women interacting in scenic landscapes, broken by text dialogue. During the talk that followed the screenings, Lockhart explained that it was important to her to have the English text be separate from the Polish speaking, that she wanted the women featured in her film to “share their voices,” and for the viewer to experience the sound of their speech without distracting subtitles. It creates for a beautiful, intentional viewing and listening experience.

The question / answer period with Lockhart and Benning was more like a skit, interrupted by the occasional question. The filmmakers are longtime friends, colleagues and collaborators, and they teased each other at the front of the room.

As the evening concluded, people lingered in the Hall and the lobby downstairs, chatting up Lockhart and Benning, and savouring the last seconds of their charm. We left the Western Front a little more observant than before.