“This is gonna sound fucked up but do you remember the girl Rolando was with?” “Yeah, Timika?” “THAT’s Timika Laqué? Oh my god, it’s a real person…” “There’s a story that goes along with that.” Sitting on the pavement outside by 868 East Cordova, where a large mural by the AA Crew is housed, Jay Swing, Flipout and Dedos have an important detail of the first issue of Elements Magazine to flesh out; 25 years after its publication in May 1995.

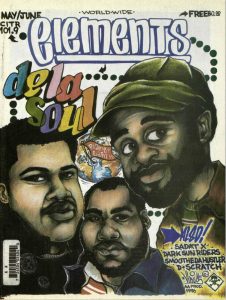

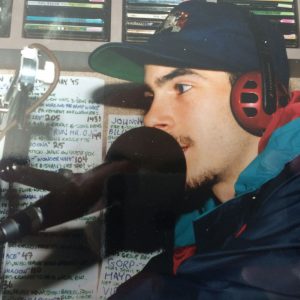

Elements — extending out of the CiTR station — ran until Winter 1996 and focused on encompassing all the elements, so to speak, of Hip Hop culture: MCing, DJing, B-boying and graffiti. DJs Jay Swing and “Flipout” (Phil Cabrita) had already established themselves at the station as hosts of “The Show” with Checkmate at CiTR every Saturday night from 6-8PM, before approaching station manager, Linda Scholten, with their idea for the magazine. The functioning core was made up of Flip and Jay — who handled everything from the editorial duties, the layouting, to the distribution — with AA Crew members, Dedos and Virus, who contributed the lettering and graffiti-style illustrations. Now, those behind Elements come together again to wrap things nicely into a book that collects all the little pieces to the magazine.

The magazine boasts features with some prolific MCs in the industry — like Raekwon, KRS-One, OutKast and Ghostface Killah, and with DJs in their “Vinyl Conflict” columns such as Red Alert and Stretch Armstrong”. Each issue contained album reviews, a ‘mixtape’ of songs, and the “Masterpieces” column to spotlight worthy graff coordinated by the AA Crew, who were also running their own ‘graff-zine’ at the time called Xylene. Going through the eight issues the crew produced, you find little pockets that delve into the thoughts and lives of people within that community; in the editor’s notes, in Mr. Bill’s ruminations in his “Metaphysics” column on the state of the scene, or in Checkmate’s assertion of the language he uses in Issue 4 under “Y’knowwhati’msayin’.” It’s a brief look at this culture scarcely documented in Canada, at a time when content wasn’t as readily accessible and our duties not so streamlined. “We were still fucking printing them out and pasting them on boards at that point,” Flipout says of their process “it would take us so fucking long to do this shit, too.” In every mention of Elements that I have seen, there has always been reference to their difficulties with meeting publication deadlines. Flipout’s editor’s notes were often frank about their issues with getting to print on time, and Jay says “we ratted ourselves out. If we’d never said that, I bet people wouldn’t have even known that it was late.” Ultimately, the delay contributed to the end of their run, “The next issue started to get worked on,” Jay explains, speaking of the never published Issue 9, “I kept getting mad because we wouldn’t go out to make another one, […] too much time went past. We were always late, late, late and finally, it was obvious that it was just way too late.”

Not only were they coordinating every administrative aspect of the magazine, they were also writing a majority of the pieces themselves. Doing all of the work on their own became overwhelming, especially when this was something they were not profiting off of. “We were doing it for fun from the beginning, we kept doing it for fun, and then it became a lot of work for Jay and I.” A lot of the pieces from the first issue are penned by Flip and Jay, so much so that Rolando Espinoza — the editor on the first issue — decided it would be a good idea to list some under aliases. That’s where Timika Laqué comes in; as one of the ‘credited’ writers on that issue. “He chose his girlfriend’s name for one thing that I wrote, but I happened to diss K-OS in that. I said he sounded like that kid who thinks he’s Q-Tip, and then K-OS got pissed.” Jay recounts, “And K-Os is my guy, but back then him and Ghetto Concept wanted to confront Tamika about the diss. When they found out that Timika Laqué was Jay the White Guy then they were really pissed and confronted me out in front of the York Theatre at the Hip-Hop Explosion Tour. They were like ‘You fucked up, bro. We are trying to build something here and you just put a crack in the foundation. Why would you do this and why would you change your name?’ I’m like ‘This sounds like an excuse, but it was the editor before we went to print! It was such a bad look. It was also a real uncomfortable situation.”

The issue of contributors persisted while the magazine was in publication. There was little interest coming in from other Discorder/CiTR volunteers in writing for Elements, and they still couldn’t get themselves paid through this work, no less, pay others who they wanted to write for them. “Rolando did say ‘try to get more diverse contributors.’ We tried, but then no one could be paid,” Flipout says, and Jay summarizes the sentiment stating “You couldn’t pay somebody to do the work — and it was a lot of work — so we just did it.” There was an interest in branching off from the station and its non-profit structure, but that proved difficult. Past a certain point, they couldn’t really justify the sleepless weeks that would go into putting out an issue they couldn’t get paid for either. The lack of contributors, the institutional strain and absence of pay, all contributed to the decision to fold — though the same could be said for the urban BIPOC youth whose self-expression breathed life into the scene, and into Elements pages.

It was a funny time to be having this conversation with people who ran a magazine through CiTR before I was born — because it’s one we have been circling back to within Discorder — the defining line between work that is solicited, and that which is volunteered. Our position as an outlet which provides opportunities to volunteer; to learn, and to make, but further, to have work published — and what then, is considered fair under our particular structure. It’s been something I have had to reflect on, in thinking of what my role as an editor has traditionally been defined to consist of, and the ways in which I could (and should) reconceptualize the work I do to to better align with what it actually means to be equitable and accountable.

In discussing the distribution of work, I wondered how much of that could have been avoided if others in the station had been more involved. Interestingly, Jay and Flip tell me that it’s hard to tell. Especially now, decades after the fact, how much of that was lack of interest and how much of it was them being unapproachable. “I think a little bit, too, maybe we were not that inclusive. We weren’t that open, you know?” Flip considers, “I went through all of my 20s with this weird chip on my shoulder about anything. I kinda didn’t wanna hang out with people, and was like ‘We’re  doing this shit, you’re not a part of this.’ There might have been a little of that from my end.” In a way, it makes sense. Looking at it from the perspective of 20 year olds’ overprotective disposition towards something they’ve initiated, and that feeling of it being an extension of themselves. “If it was me now, I would be asking everyone ‘yo, do you wanna be a part of this?’, but back then we were like ‘We got this. We know what we’re doing […] You would’ve fucking hated us. It was peak… white guy in the 90s. I don’t think I was very cool then, at all.” Flipout also admitted that sometimes that sentiment was justified — recalling an old argument, “Fuck I feel so dumb. I was arguing with this girl, she was saying “hip hop is political” and I responded with “no it’s not, it’s just about youth expression”. I got very defensive — but we were actually saying a thing, and, like, she was right,” he says laughing.

doing this shit, you’re not a part of this.’ There might have been a little of that from my end.” In a way, it makes sense. Looking at it from the perspective of 20 year olds’ overprotective disposition towards something they’ve initiated, and that feeling of it being an extension of themselves. “If it was me now, I would be asking everyone ‘yo, do you wanna be a part of this?’, but back then we were like ‘We got this. We know what we’re doing […] You would’ve fucking hated us. It was peak… white guy in the 90s. I don’t think I was very cool then, at all.” Flipout also admitted that sometimes that sentiment was justified — recalling an old argument, “Fuck I feel so dumb. I was arguing with this girl, she was saying “hip hop is political” and I responded with “no it’s not, it’s just about youth expression”. I got very defensive — but we were actually saying a thing, and, like, she was right,” he says laughing.

Parts of Issue 9 will finally get a home nestled among all the other fragments, including an interview Flip did with Jay-Z in ‘96 before his first album came out which he claims to be a “Terrible interview. If you hear the audio, it’s cringe max,” with Jay coming to his support to say that it “reads a lot better.” Along with that, we can expect a big showcase of Dedos’ unreleased artwork. Speaking to this renewed interest in their work with Elements, Jay says “Whenever we’d post stuff, people would be really into it. It really sparked some nostalgia, and more importantly, fuck all that, it would spark something in people. People like you, who weren’t even there, who were like ‘What is this artefact — this time capsule?’” This an opportunity for them to bind those experiences into one substantial thing that cements what truly went down. This is where the magazine’s journey towards existing as its own entity culminates, years after that question of “what now, and how?” was first posed. The book is slated to come out around Christmas, if things go according to plan, but as Jay says, “we have no idea of timelines when it comes to publishing.” So, in true Elements fashion: the book will come out whenever it’s time for it to come out ?????