If punk is not dead, then it lives on through the likes of Vancouver writer Chris Walter.

A former drug addict and seventeen-year resident of East Vancouver, Walter’s embedded punk spirit maintains its discourse with anger and revolt through his self-created publishing company, Gofuckyerself Press. Over the past eleven years he has published over twenty titles, including more than a dozen fictional narratives such as Up and Down on the Downtown Eastside (2011), Punch the Boss (2009) and East Van (2004). He has also written and published a three-part autobiography, several collections of short stories, and Argh Fuck Kill (2010), the biography of Canadian punk rock legends Dayglo Abortions. A similar biography on SNFU is due to hit shelves this summer.

More often than not, his fictional characters are working class or unemployed mavericks and heroines: ravaged junkies, prostitutes on the prowl, heartless drug peddlers, debaucherous rock ‘n’ rollers. His settings frequently portray the dark realities of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and the ravenous punk scene in Winnipeg, MB, where a youthful Walter first donned a leather jacket and sculpted a Mohawk. His stories of drug-addled desperation, stage diving gone wrong, and the agony involved with relating to the status quo, are heartfelt accounts not to be taken lightly. Yet, it is no wonder that he leans his plots against a ragged narrative style steeped in the comedic dark side.

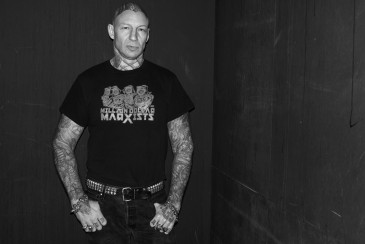

On a recent, crisp afternoon, Walter invited me to his modest, two bedroom East Van apartment for a one-on-one discussion. Despite the imposing, fully-tattooed figure that sat across from me at the kitchen table, I couldn’t help but feel at home because of his honesty, his bravery, and his passion for all things punk.

(Interview has been condensed)

What have you been up to recently?

I have a few projects on at the moment. First, I’m wrapping up a book of short stories that’s going to the printer on Monday. It’s just a small collection of stories to keep some money coming in while I finish this SNFU biography that should come out in the late spring or early summer. I started it in August and usually it only takes me—well, I put out about two books a year—but if I do a music biography then it takes me a whole year to complete it.

Tell me about the process of putting a rock biography together. What do you include? What don’t you include?

I collect phone numbers, make calls, and write chronologically, never knowing what I might uncover. Every band has at least one skeleton in the closet, and they must be handled carefully. You can’t leave it all out, but you don’t want to hurt the band too much. It’s always a judgement call.

You were there during SNFU’s rise to prominence during the ’80s and ’90s. You were living it, so describe the scene.

Beer, freedom, and loud groundbreaking music that soon gave way to hard drugs and general violence. A good time … and SNFU showed the rest of Canada that even a scummy punk band from Edmonton can rise up and tour the world.

Can you explain the connection you share with SNFU — either your connection to their music, or connections you’ve had with the varied band members, or both?

I’ve known Ken Chinn [a.k.a. singer Chi Pig] and some of the other band members, including [drummer] Jon Card, for thirty-odd years. We share a mutual punk history and an unfortunate appetite for mind-altering substances.

Has your distribution morphed through Gofuckyerself Press, as though each successful publication means more independent book shops or more music shops become interested in carrying your next publication?

It’s all one step forward, one step back. I get a new book store and then another one closes. I get a new music store and then another of them closes. It’s a constant battle. Online sales are up and down, though they’re generally improving. And now I’m even going into e-books, but that’s starting off slowly too.

Would you say the majority of your sales are online through your website (punkbooks.com) or through physical book stores and music shops?

I’d say it’s about half and half. Well, actually, I have book stores all over Canada now, so maybe I am selling a few more through those retail shops.

It was 1991 when you first arrived in Vancouver, and you got off drugs in 2001. How have you seen the Downtown Eastside change over time?

Well, it hasn’t really changed that much at all, except that it’s becoming more and more squeezed by gentrification. But the reality hasn’t changed for the residents that are living there—the addiction and the desperation are still the same. I’ve never lived right there, I’ve always lived in this building—been here for 17 years—but I’m within walking distance, so I’d be down there hanging out for days. The biggest change for me is that now, instead of walking down to get high, I go down there to volunteer at a shelter on Friday nights. Now I’m on the other side of the glass.

How easy was it for you to get help down there ten years ago?

It’s about the same as it is now, I guess. The First United Church building is that kind of shelter-from-the-storm that you can go in to no matter how messed up you are. At one point I needed new teeth, another time I needed help because I was being cut off of welfare, and then they were trying to throw me out of this place here and I needed arbitration. As an addict, my life was always in constant drama and every time I found myself in the real shit I’d go down there and I’d get an advocate to take care of it for me.

What sort of hope do you have for the DTES these days?

To be honest, we’re not going to see an end to drug prohibition, but if we could then that would be my hope. Realistically we need more housing, and if drug prohibition is going to continue then there’s always going to have to be a place for addicts in any city. As bad as the DTES is, at least there’s a lot resources there for them. If the city decides to spread them [the addicts] all over the city then they won’t have those resources available to them and it will be even worse if everyone gets kicked out and moved farther east… They actually advertise these new condo complexes in the DTES and I remember one that said, “get a loft in the real world” [chuckles]. I imagine the people coming down to have a look while stepping over piles of human shit. Their cars would get broken in to three times a week and I guess they would say, “Oh, this is the real world.”

It’s that real world that attracts myself and others to you, or Bukowski, or to George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London. The rest of the world seems so contrived, so fake on so many different levels that the agony, the pain, and the loneliness that openly exists in a place like the DTES is a fading glimmer of what is real.

Yeah, and another thing about the DTES is that everybody knows everybody. Everyone knows your name and your game. It’s like a tight small town. I still see that when I go to volunteer at that low-barrier shelter.

What’s your feeling about the police officers that are working the beat down there?

The cops we see are generally a pretty decent bunch. There are cops I know that are assholes, just abusing their authority, but most of them are okay. Of course some of them don’t really have a brain —those are the assholes. But the ones with half a brain can see that this is an example of how drug prohibition doesn’t work. They know that if they actually took everyone into booking for all that shit then the system would be so jammed up. They realize the logistics of it, like busting people for pot — isn’t that insane!

Yeah, it really surprises me that a lot of people still don’t understand that.

The general public doesn’t have a clue about what it’s like down there, about what addiction is actually like. The only time they ever get the smallest glimpse is if a friend or family member becomes addicted. And while they might not catch on at first, then things start going missing, and then comes the weird behaviour, and then the person either OD’s or goes to jail, or becomes homeless, and then the family realizes, “Holy fuck, so that’s addiction.”

How was your party scene and your drug abuse connected to music?

Well, there are a lot of punk rock junkies and a lot of them come from a place where they want to be a rebel and break rules. Of course some of their idols were addicts that used all that stuff. I mean, if you use Sid Vicious as a role model then you’re going to wind up in trouble.

Have relationships with your friends changed because of how you’ve portrayed them in your narratives?

I don’t really take one person and put them in a book. I think all my characters are an amalgamation — a bit of this person, a bit of that person. None of my friends or my ex-friends would be able to recognize themselves. I wouldn’t do that to them; it just wouldn’t be cool. And anyways, a lot of the people that I used to use drugs with have either cleaned up or are dead. Some of them are on methadone and just coasting along. Very few of them are still in pieces when I see them down at the shelter, but they really are in terrible shape. And that’s such a strong motivation for me to not get high because then I’d be on the other side of that window, with shoes that are falling apart in November, and looking and smelling like shit.

What about writing as therapy?

Oh, for sure! It keeps me busy, it makes me happy, and it provides money too [laughs]. I did start writing just before I cleaned up and I even used my first laptop as collateral with the dealer. I’d say “keep this and when I get some money then I’ll come back and get it.”

Chris Walter’s publications can be found on shelves in independent music and book stores across Canada, or they can be ordered through his website, punkbooks.com