Where to start?

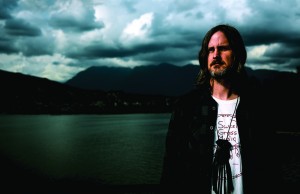

I pick up Kevin “Sipreano” Howes in Mount Pleasant to drive to Third Beach. His choice of location. We talk about defunct venues and media arts. Then the conversation breaks for a moment while stopped in traffic, and it suddenly occurs to me that we are getting farther and farther away from the huge collection of vinyl records that seem to define Howes’ public image. Is this distance purely physical, or is it psychic as well? How essential is his association with vinyl? I decide not to bring it up. Once at Third Beach, the backtrack of our interview is a percussion of waves and crow calls, and that’s all the rhythm we need.

“The most meaningful music to me is something where the vibrations are a lot stronger … It is a holy experience being able to connect with music, and connect with art, and connect with nature,” shares Howes. As if addressing my initial thoughts, he adds, “I want to keep digging, as deep as I can, to learn more about the roots of it all … It’s mostly about the music, not really about the format, though vinyl is what I work with.” The music that Howes appreciates is from the initial vinyl era between the 1950-90s.

Howes began DJing as Sipreano in the mid ‘90s, merging interests in reggae, r&b, hip hop, jazz, jungle, folk and psych to host open genre parties at venues long-gone. Most notable among these regular nights was “The Soulcial” at the Chameleon Urban Lounge with Neil Frost, a.k.a. Kamandi. “I feel like open format was something that came out later with the internet,” explains Howes. “Everyone was in their camps before — the metal heads, and this and that — but [Kamandi and I] always appreciated stuff that resonated with us regardless of the background, or whether it had commercial success.”

Throughout the ‘90s and early ‘00s, what started as an interest in open genre music and record collecting grew into an obsession with sound heritage and archiving. Howes expanded upon his appreciation for the music, and began researching historical context and social significance. With the guidance of mentors and collaborators he met while travelling the United States, Japan and the U.K., Howes leveraged his knowledge to present eclectic live performances locally and internationally, record mixes for companies and art collectives, and bring research to music projects. In 2003, Howes met Light In The Attic Records co-owner Matt Sullivan, and began working with the label as a consultant, researcher, and liner notes contributor. Their collaboration resulted in the influential Jamaica to Toronto: Soul Funk & Reggae 1967-1974 released in 2006, and more recently, Native North America Compilation (Vol. 1): Aboriginal Folk, Rock, and Country 1966-1985 released in 2014.

Howes estimates that he has given close to 65 interviews about Native North America. I try to avoid discussing it, but it’s impossible; Native North America is Howes’ most high-profile project to date, earning him and his collaborators a Grammy nomination and international praise. In addition to three records, the box-set compilation includes a booklet of interviews with the featured artists, none of whom found commercial success among their contemporaries. Though the music is 20-40 years old, the themes expressed ring true today — hard feelings over the loss of nature to industry, and the loss of family to government. In an era of accelerated environmental destruction and the first attempts at reconciliation, Native North America is a timely project. Yet, there is a lightness and beauty to the music —

“Native North America raises a lot of issues, a lot of concerns, but it is also love. And hope. And caring. And compassion. And humanity,” says Howes. “It covers the gamut of human expression, and specifically indigenous expression. It’s easy to latch onto the bigger themes, but there are love songs, too.”

Howes wrote the introduction to Native North America, signing it with his full name and the title, Voluntary In Nature. When I ask about the meaning of this term, Howes describes it as his “cultural umbrella.” It is a phrase borrowed from Jerry Garcia — In 1970, Grateful Dead performed a free outdoor concert in Toronto after protests that their scheduled festival appearance was too expensive. Garcia described the efforts of the organizers, performers, and staff as being “voluntary in nature.” It wasn’t just about the money. This concept resonated with Howes, inspiring the name of a soundscape mix for Sandinista Clothing & Apparel in 2006, and later, Howes personal blog at voluntaryinnature.blogspot.com in 2010 that is still updated today.

On the topic of blogging and web presence, Howes says that he likes to keep it “pop and in-the-moment.” He continues, “Everyone in the digital age collects information about themselves, whether it’s photos or Word Documents or Excel spreadsheets, or any number of ways you can save imagery, data, thoughts. Some people share it, some people keep it personal the way you would a photo album back in the day.” I ask Howes if he considers his blog posts as contributing to an archive of sorts, and somehow our conversation shifts to a question of physical versus digital, and consumerism —

“I question the physical product today, in the modern age, when we’re surrounded by so much waste. In a digital world we don’t need to create all that waste” laments Howes. “I’m evolving in my career so that I would like to put out some records and work on archival projects of my own, but I only want to put out something that I feel merits the waste, merits the materials that they would be printed on.”

Touching on the craze for vinyl as nostalgic gimmick, Howes continues: “The reissue market today is so over-saturated. People are putting out everything, thinking, ‘Oh, it’s from the past, it must be good.’ I don’t think that everything from the past is worthy of reappraisal. In fact, I think a lot of things are best left to the past.”

Our dialogue is interrupted suddenly when we spot a crane on the beach. The focus of the interview shifts back to our immediate environment. Howes attributes his appreciation of Third Beach to Chris Frey (Radio Berlin, Destroyer) and Steven Balogh (Pink Mountaintops, Anemones) in the mid ‘90s: “They encouraged me to come down to the beach, even on grey days, to come down here and have a beer, smoke a little grass, and go swimming.” But Howes’ friendships with Frey and Balogh had an impact that extended beyond physical activity —

“Their influence to reconnect with nature and the ocean was really important. I was making music at the time, a lot of sample-based collage music. I was connecting with all these things, and going back to nature and friends. It was voluntary, really. I was surrendering to it and reconnecting to it. When I came to these places, I would really start listening to the environmental sounds, listening to these rhythms. It was so affecting. I would go to the woods and take walks. I was listening to a lot of folk, French Canadian and psych music, too,” explains Howes. “Voluntary In Nature is a reflection of my reconnection with nature and how I’d like to approach the business which I find myself working in.”

In everything he does, Howes is a collaborator. In partnering with other researchers, musicians or like-minded labels, or seeking out natural rhythms, Howes establishes himself as curator and archivist. Howes knows what people want, even before they do. Through sound and setting, he creates the perfect mood.

X

Read more about Howes’ past and upcoming projects at voluntaryinnature.blogspot.com, or listen to some mixes at soundcloud.com/sipreano. And keep an eye out for his next DJ night at The Lido.