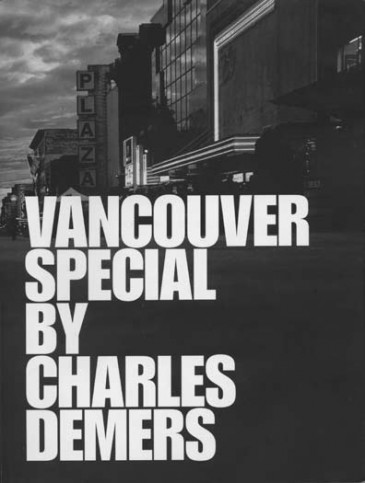

Vancouver Special is a well-researched collection that begins with neighbourhoods, moves towards peoples and then to movements and issues that are prevalent, including “Vanarchism,” “Racism” and “Homes.” The simply titled essays are accompanied by bold yet stark black-and-white images by Emmanuel Buenviaje.

There’s a nostalgia that runs through Vancouver Special that’s pointed to in the introduction of the book. As Demers explains, “This is a book … written on the eve of the 2010 Winter Olympics by a Vancouverite who grew up with and after Expo ’86.” And now the Vancouver between Expo and the Olympics is at risk. Exploring its past is the best way to prepare for the future.

But what makes Vancouver Special a gem is that in his exploration of the place he grew up, Demers exposes himself and his history. This disclosure informs the cultural and political slant of the book, but more importantly, the reader gets a sense of who Demers is without the overexposure often found in fullout memoirs. His use of (often) self-deprecating humour and examples from his own life illustrate his topics rather than detract from them and they add colour to what could have been drab academic essays. Take the essay “Pot.” Demers tells the story of successfully buying marijuana seeds when he was 15, when he was “so doughy as to be circular, with a silken blond mushroom cut like the shortstop on a lesbian softball team.” This self-description serves two purposes. Not only is the reader invited to laugh at a vision of Demers as a chubby cherub buying drugs, but that that vision of innocence could so easily obtain them—because virtually everyone in Vancouver has a marijuana connection (literally and figuratively).

I often found myself laughing aloud while reading the book, especially at Demers’ observations of what any Vancouverite knows to be true Vancouverisms. In describing the Naam, for instance, he points out that “on Friday and Saturday nights, after the shows and the clubs let out, the patchouliati are joined by the chachi nightclub crowd, and the smell of incense mingles with that of Joop! and Right Guard.”

Demers’ comedic wit is obvious throughout the book, even when dealing with difficult topics. In “First Nations” Demers tells his reader about Chief Dan George and E. Pauline Johnson, cultural figures revered by Native and non- Native alike, along side that of Frank Paul and the disappearances of women from the Downtown Eastside, emblems of the racism towards aboriginals in Vancouver, to show the dichotomic relationship the city has with its original inhabitants. But Demers jovially admits to feeling insecure about being a white guy writing about these issues, saying, “What if I spelt something wrong, marking me as a racist?”

Demers also draws from other local comedians, placing their hilarious annotations of the city throughout the book, such as Erica Sigurdson’s note that she doesn’t have kids because she doesn’t have “the uniform for moms in this city—head-to-toe Lululemon.”

A topic that runs throughout the course of the book is Vancouver’s political climate, both today’s and throughout its history, especially in regard to labour. What else could we expect from a man who repeatedly describes himself as a young Trotskyite? It’s easy to forget how politics shape culture but Demers’ extensive research reveals much of the city’s political influences, whether it’s the controversy over highways in the 1970s, the Woodward’s squat in 2002, or the 1912 protests by the Industrial Workers of the World that followed the city’s ban on their public speeches.

Vancouverites and non-Vancouverites alike will learn something from the smart and witty essays in Vancouver Special. Locals will appreciate seeing their lifestyles reflected back, and both them and foreigners will get a glimpse into what makes Vancouverites tick. As well, they will be introduced to an up-and-coming Vancouver personality—I’ll probably run into him on the bus home.