“You poor creature… have you nowhere to go? No one to love you? You poor creature… will anyone miss you?”

When these words are uttered in Brendan Prost’s new short film, Heavy Petting, the viewer thinks they understand. They believe they’re hearing a woman project her own emotions onto another; they trust that these words are a wounded person’s attempt to deny the severity of their own condition. And to some extent, this is true — but that’s not the point of this film. The point is to highlight the horrifying ways in which it’s not.

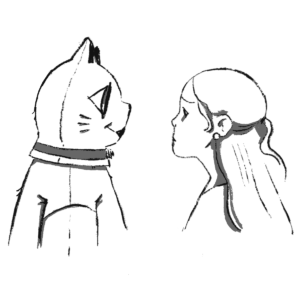

Heavy Petting begins with the story of Marina (Haley Midgette), a woman who has recently lost her beloved pet cat. We see her searching hopelessly around her neighbourhood, to no avail. She looks drab at a banal work meeting, and lost in her now companionless home, attempting to fill the void of loneliness with masturbation. Each new frame communicates a grim, inescapable sense of loneliness — until a chance for connection suddenly appears. Marina opens the front door of her home to see a person crouching on the lawn, donning a costume that looks as if it could be Chuck E. Cheese’s morbid feline relative.

Despite the absurdity of the situation, Marina allows the cat impersonator into her home, taking comfort in the opportunity to resume the role of caretaker. Eventually, the nurturing elements of the encounter descend into the erotic, and the cat costume is removed to reveal a woman named Jordan (Sam Calleja). The two share a passionate night together, and given the bizarre circumstances which led to their meeting, viewers are left to assume that it’s the beginning of a unique relationship. A love story, even. But that’s not the story Prost set out to tell.

Hours later, Jordan’s efforts to translate the peculiar tryst into a relationship that see’s daylight is met with Marina’s cold rejection. As Jordan leaves, Marina’s lost cat scurries through the front door, putting an abrupt end to the state of loneliness that prompted her to allow a stranger into her bed in the first place. As Marina rejoices over the return of her pet, we see her in a new light. As a smile washes over her face, we recall her steady job, her tastefully decorated home — it becomes plain to see how the return of her cat is enough to infuse light back into her world. When Marina caresses Jordan, referring to her as a “poor creature,” we initially feel as if this description is equally applicable to both women. But the latter half of Heavy Petting obliterates this assumption, drawing a stark and terrifying distinction between Marina and Jordan’s worlds.

Illuminating this distinction — that is, the distinction between transient loneliness and ineluctable desolation — is the core of the film, and it’s achieved in a shocking and unforgettable manner. The film’s bifurcated format may be jarring to some, but it seems to me that jarring is precisely what Prost was aiming for. By splintering the story in two, viewers are forced to contend with the false assumptions they made in the first half of the film. We realize that for Jordan, the antidote to misery isn’t as simple as the return of a four-legged friend. What she’s experiencing is more than a fleeting absence of connection, rather, it’s a prolonged state of alienation, a state which has penetrated her sense of self, shaping the way she navigates the world. In the latter portion of the film, we see her go to great lengths to cope with this condition, committing acts that may seem grotesque and unjustifiable — but isn’t the acceptance of such complete desolation just the same?

Heavy Petting is an uncomfortable watch, and not just because of its unabashed bizarreness and eerie score. It’s uncomfortable because it aggressively confronts viewers with a truth that we’re all, to some extent, already aware of: that people such as Jordan exist all around us, and hardly anything is being done about it. And of course, the film is likely even more harrowing for those who see themselves in Jordan. Isolation and depression plague the modern world, and in the midst of a global pandemic, there seems to be more awareness of this fact than ever before. And yet, advice on how to remedy the situation still feels unsatisfactory. It often boils down to: “reach out to your support system: family, friends, partners.” This may be adequate for people like Marina, people who have someone to turn to. But Heavy Petting questions what exactly is to be done for people who don’t.

Prost has stated that the film will resonate especially with queer audiences, who “know the sting of fetishization better than most,” and it’s plain to see why upon viewing. Marina lets Jordan into her world in a moment of desperation, allowing herself an erotic, euphoric queer encounter — but just for one night. Down the line, she may look back on the evening with shame, embarrassed by the lengths she went to aid her loneliness. Or perhaps, she’ll recount it to thrill a new boyfriend, using it as evidence of a risque wild-side she’s now grown out of. But for Jordan, the evening was a brush with intimacy, a peek into a seemingly unattainable life, a glimmer of hope followed by a predictable discardment.

Heavy Petting offers no answers, and no respite. Instead, it asks viewers to sit with their discomfort, to reflect on the gravity of a condition they may be accustomed to turning a blind eye to. Some may feel this is an unproductive approach to film-making, that Prost should leave viewers with a small trace of hope, or an indication of how to proceed. However, I disagree. Mental illness and isolation are often silent and invisible ailments, causing immense pain that is essentially imperceptible. Heavy Petting not only succeeds in shining a light on this pain, but in utilizing the macabre to ensure viewers don’t forget about it.