In February 1983, Jennifer Fahrni and Mike Mines published the first issue of Discorder. That means we are nearly 30 years old. In the next four issues, we’ll tell tales that harken back to the days of Discorder yore. Here’s one from the early ’90s.

Song lyrics were a big deal in the 1980s. Amidst Reaganism, Thatcherism, televangelism, and conservative “isms” of other sorts, the ‘80s were marked by outrage at the potentially damaging effects of popular music. While organizations such as the Parents Music Research Center (PMRC) concerned themselves with attempting to stop morally objectionable music from infiltrating the sanctity of the American family, the more “progressive” side of the political spectrum had concerns of its own. Progressive strides made throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s had heightened awareness of hate speech, which many felt had the power to incite abuse or violence. By the late ‘80s, a crop of politically charged rap artists were making themselves impossible to ignore, both by Christian conservatives and arbiters of political correctness on the left.

Artists like N.W.A. and Ice-T unabashedly exposed aspects of the urban black experience to the culture at large, addressing a society they felt left many black youth with little recognition and even less opportunity. While many saw the broader hip hop culture as a positive move towards expression and self-determination, some rap artists were fielding charges that their lyrics glorified racism, misogyny, homophobia, and violence.

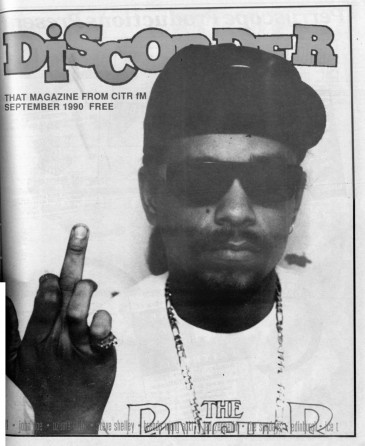

In this climate, perhaps it was appropriate that the cover of Discorder’s September 1990 issue, featured an image of Ice-T giving the finger to the camera. In the interview, Ice-T answers for his own use of the words “nigger” and “faggot,” and saying, “…there’s never been one documented case of a kid listening to a rap album and committing a crime or a kid listening to a 2 Live Crew album and raping somebody.”

That same issue featured an interview with Sonic Youth’s Steve Shelley, who spoke to the issue of music censorship as well as discussing the “SMASH THE PMRC” logo as the cover art for their album Goo. The issue also featured an extended, very tongue-in-cheek piece by Discorder writer The Man Sherbet that pointed to the fact that much of the classic rock that groups like the PMRC had grown up with, long revered as innocuous cultural treasures, contained potentially offensive (often misogynistic) lyrics, as well.

But perhaps more than any other artists, it was Public Enemy who raised the political stakes of expression in rap. In a May 1989 interview with the Washington Times, Public Enemy’s “Minister of Information,” Professor Griff, among other things, declared that Jews were responsible for “the majority of the wickedness that goes on across the globe.” The comments caused a firestorm, adding to the myriad controversies already surrounding the group. Chuck D denounced the remarks and ultimately fired Griff.

Released in March 1990, Fear of a Black Planet featured what was perhaps part of Chuck’s response to the controversy in the song “Welcome to the Terrordome:”

Crucifixion ain’t no fiction

So called chosen frozen

Apology made to who ever pleases

Still they got me like Jesus

The lyrics only intensified the charges of anti-Semitism, though Chuck assured the press that that was only one interpretation of the lyrics and “not what [he] was thinking.” In the lead-up to a CiTR-sponsored Public Enemy concert at the Orpheum Theatre on August 30, 1990, a complaint was filed to then-UBC President David Strangway by a member of the Vancouver Jewish community, expressing concern that UBC was funding a radio station that had chosen to support such an event. UBC released a position statement, noting the delicate balance between free and responsible expression, and promised to set up a Task Force on Race Relations, examining related issues across campus. The concert went on as planned.

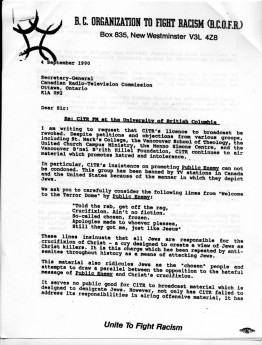

Within a week of Public Enemy’s concert, CiTR held its first hip-hop competition, DJ Sound Wars, to support the Pacific Northwest’s fledgling hip-hop community. But soon after this celebration and the release of Discorder’s Ice-T cover, then-CiTR Music Director Chris Buchanan received a letter dated September 4 from the BC Organization To Fight Racism. BCOFR Secretary Alan Dutton stated, “CiTR has demonstrated a flagrant disregard for Canadian broadcast policy by airing and sponsoring the work of Public Enemy — a group well known for promoting racism and religious intolerance.” The BCOFR had written directly to the CRTC, requesting them to immediately revoke CiTR’s license to broadcast.

In her response letter to Mr. Dutton, CiTR Station Manager Linda Scholten cited CiTR’s music policy “not to air any material which includes any verbal utterances that promote discrimination or hatred against an individual or a group or a class of individuals on the basis of race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, gender, age, mental or physical ability, sexual orientation, or occupation.” She went on to assert that “Welcome to the Terrordome” was not in breach of this policy nor CRTC regulations condemning the incitement of “hatred or contempt towards any individual or identifiable group,” couched under the heading of “abusive comment.” She said that the song is a summary of the Professor Griff controversy — which she described as “repulsive” — and when examined in its entire context is clearly strongly opposed to violence. She also pointed out that Public Enemy declared their opposition to racism of any kind at their recent concert and, as a group, work to attack racial oppression. Later, speaking to the Ubyssey, Scholten echoed Chuck D’s sentiment, saying the song is open to interpretation and not “implicitly anti-Semitic.” In the interest of open discourse, CiTR offered airtime for people to voice concerns over the song, something Scholten said no individual or group chose to do.

In an early letter to CiTR concerning the issue, the Secretary General of the CRTC said that they were not a censorship body, but were there to see if there is blatant violation of regulations. Ultimately, the CRTC agreed that the song did not breach the abusive comment regulation and agreed that the overall nature of the song was one of anti-violence.

Though not much ultimately came of CiTR’s brush with the political controversies of rap lyrics — they didn’t lose their license — the incidents highlight the ground between free speech and dangerous speech that the station and this magazine, as part of their responsibility as media, have had to tread ever since. In a broader sense, and given more recent international events, the careful negotiation of this ground is still pertinent to us today.

A month after the Ice-T feature, Discorder followed up in October 1990 with a two-page spread entitled “Don’t Believe The Type: Chuck D Speaks,” including quotes from Chuck D on everything from the media to the role of gangsta rap in communicating the black experience. For their part, CiTR, in a typically tongue-in-cheek move, printed a small run of black t-shirts with CiTR’s version of the Public Enemy bullseye logo and the phrase “Fear of a Black T-Shirt.”